CHRISTIAN HAKALA WEAVES the story of the bank robbery with the skills of a seasoned storyteller, his voice rising as the tension mounts, his hands gesturing, his eyes locking with those of a rapt audience.

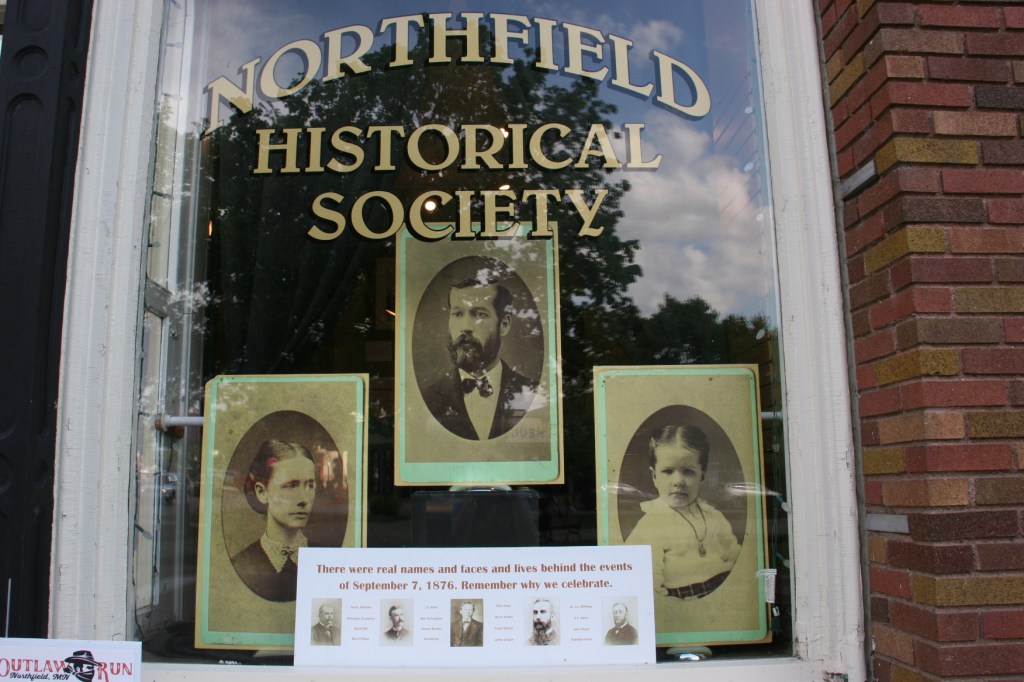

Looking through a front window of the Northfield Historical Society museum toward Division Street.

It is Sunday afternoon and I am with a small group touring the Northfield Historical Society. I have come here with my husband to view the temporary U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 exhibit as it relates to Rice County.

The James-Younger Gang re-enactors riding in The Defeat of Jesse James Days parade perhaps five years ago.

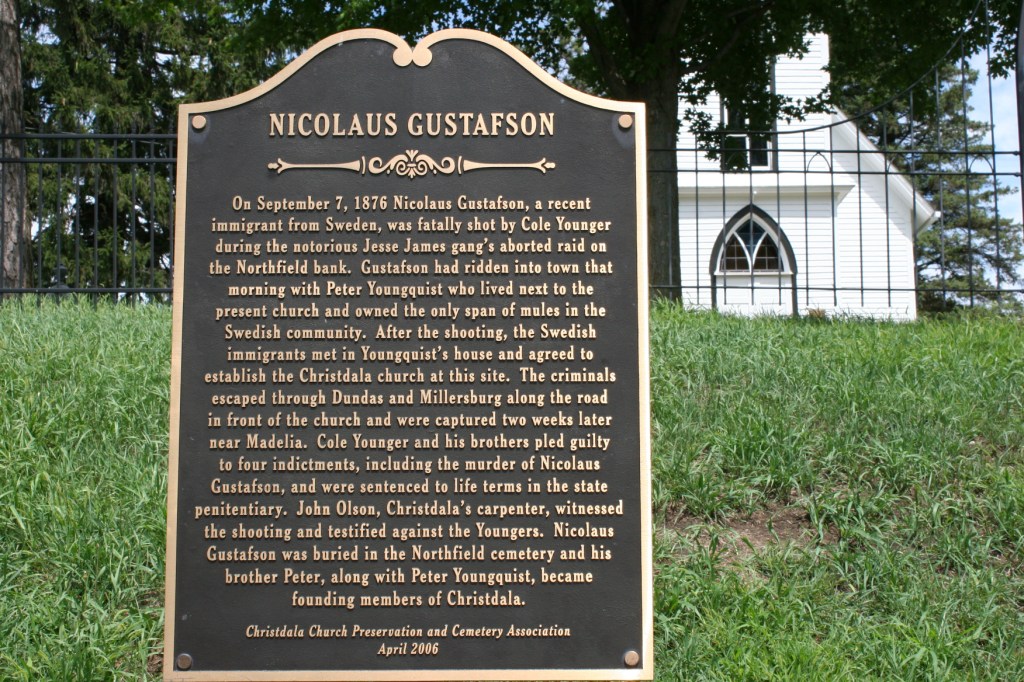

But I find myself, instead, captivated by Hakala’s intriguing play-by-play account of the James-Younger Gang bank robbery of September 7, 1876, as he leads us through the historical society and into the bank. I am embarrassed to admit that I’ve never visited this museum, site of perhaps the most historic bank robbery in U.S. history, even though I live only 15 miles away and once worked briefly as a newspaper reporter in this town.

This week some 100,000 visitors, according to Hakala, are expected in Northfield for the annual Defeat of Jesse James Days celebration September 5-9.

Christian Hakala talks about gang members involved in the Northfield bank raid, pictured to his left: Frank and Jesse James; Cole, Bob and Jim Younger; Clell Miller; William Chadwell; and Charlie Pitts.

The former history teacher, and now a fund raiser at Carleton College in Northfield, serves on the historical society board, volunteers as a tour guide and role plays a townsperson in the annual re-enactments of the bank robbery. His knowledge of the crime is precise, right down to the minute on the original bank clock, stopped at 1:50 p.m., the time of the deadly and unsuccessful robbery.

The front of the original First National Bank of Northfield. I didn’t photograph the entire building as the sidewalk in front of the bank was torn up and blocked for installation of sidewalk poetry.

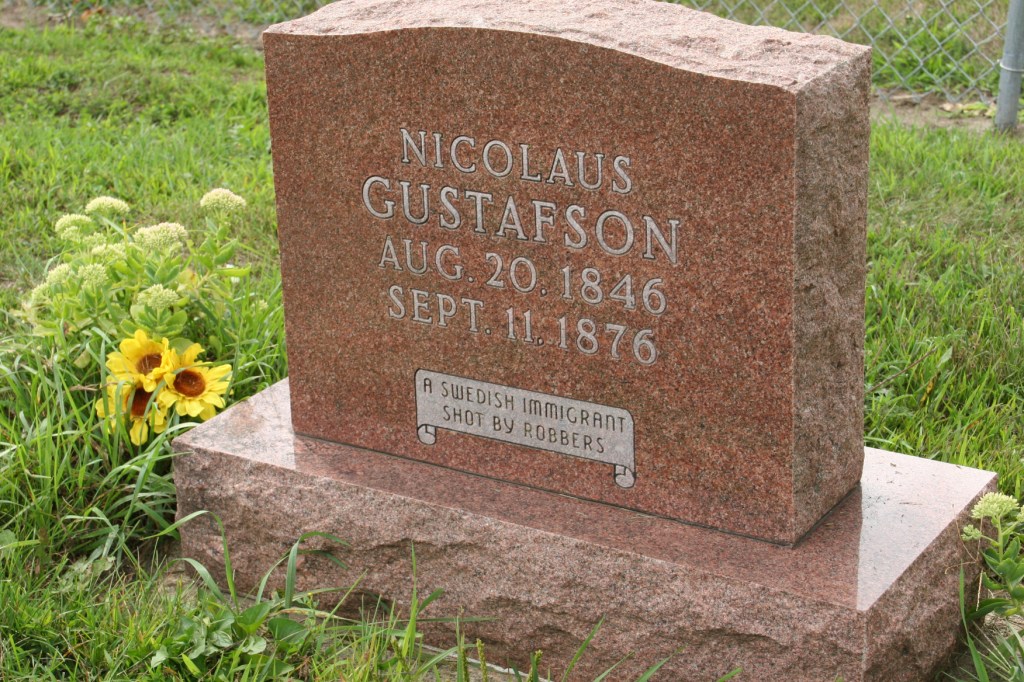

It was all over in seven minutes with four shot dead, including acting cashier Joseph Lee Heywood who refused to allow the robbers into the vault; Swedish immigrant Nicolaus Gustafson; and outlaws Clell Miller and William Chadwell.

The gun confiscated from Cole Younger when he was captured two weeks later near Madelia. I shot this glass-encased weapon in available light, without a tripod and without flash, meaning quality is not there in this image.

Not until the end of the tour does Hakala reveal that efforts are currently underway to exhume and determine if the presumed body of gangster Miller, buried in his home state of Missouri, truly is Miller.

Hakala explains: Then-medical student Henry Wheeler, who shot Miller from an upper story level of a building across the street from the bank, dug Miller from his grave and shipped the body from Northfield to his Michigan medical school for dissection and study. Later, Wheeler would return the supposed body of Miller to his family in Missouri. But, as the story goes, Wheeler kept a skeleton, purported to possibly be Miller, in a closet of his Grand Forks, N.D., medical practice office. That skeleton is today owned by a private collector.

The Miller family, Hakala says, is cooperating in proposed plans to positively identify the body buried in Missouri via forensic testing. The body was badly decomposed and thus not identifiable by the time it was received by the Miller family for burial.

Wheeler’s actions, Hakala further says, would not have been all that unusual for the time period with a likely attitude of “I killed the guy. He’s mine.”

This recent development simply adds to the mystery and drama and varying versions of events and details which have long accompanied the James-Younger bank raid in Northfield. Hakala, a northeastern Minnesota native who has also lived and taught in Missouri, knows how perspectives and stories differ based on source locations.

Yet, Hakala assures that the minute-by-minute account he relates of the actual bank robbery is based on the eyewitness testimony of a bookkeeper, collaborated by a teller who also witnessed part of the hold-up.

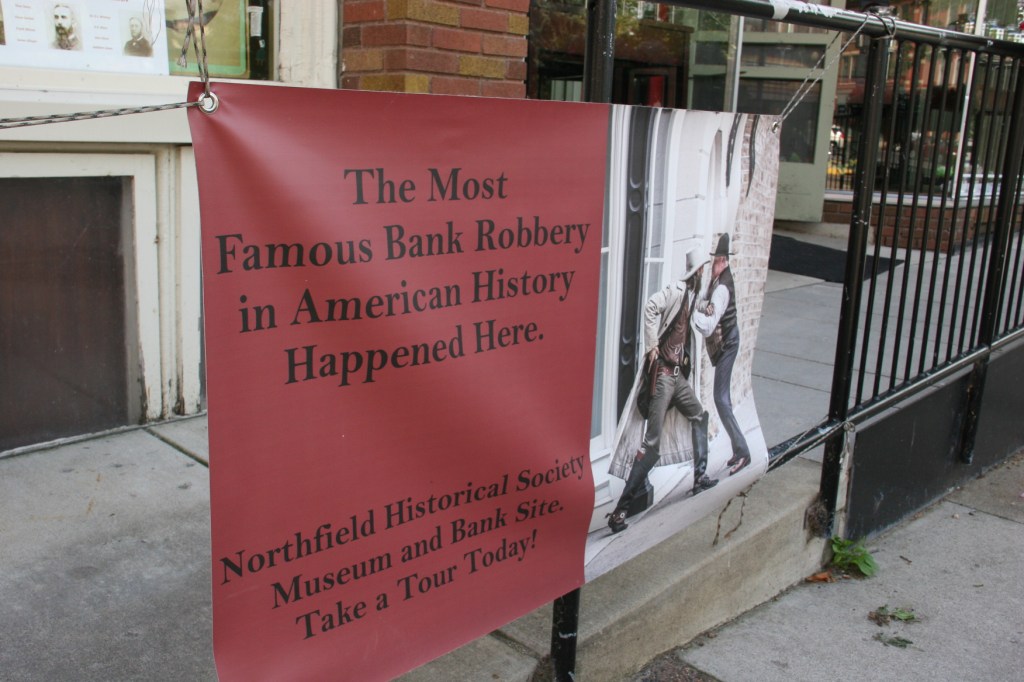

The only portion of the original bank you’ll see in this post is to the right in the background, caught when I was photographing this display case in the adjoining museum space which is in a separate building.

I can’t possibly share with you here the entire scenario Hakala presented in his tour on Sunday. Nor can I show you images, because photography is not allowed inside the original First National Bank of Northfield. But I can tell you that walking upon the very same rough floor boards trod by outlaws with a 10-year history of successful raids on trains and in banks, eying the massive black vault (closed, but unlocked at the time of the crime) and seeing blood stains on the bank ledger makes an impression.

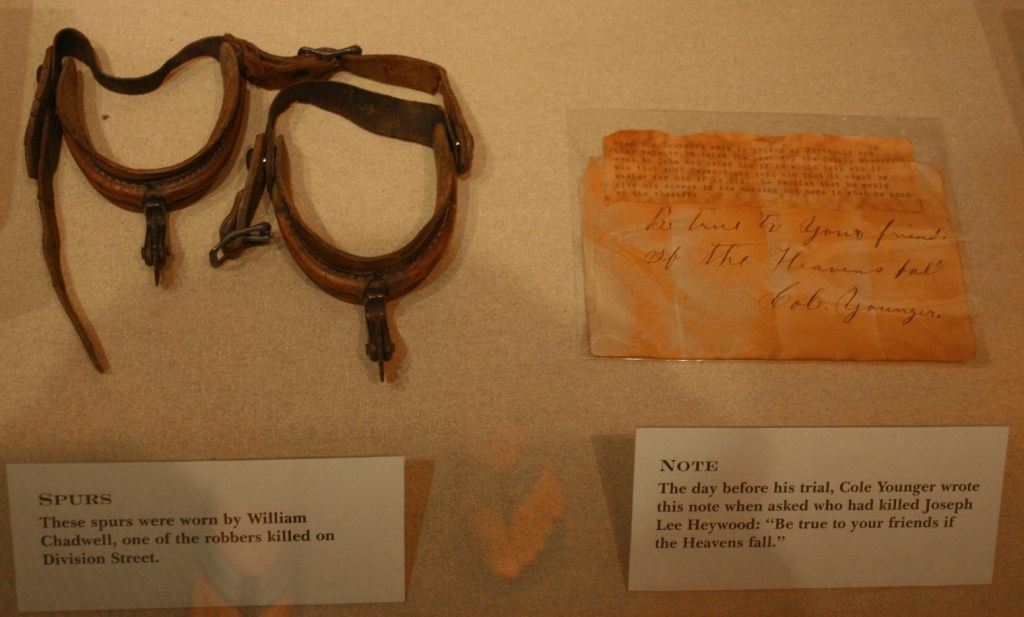

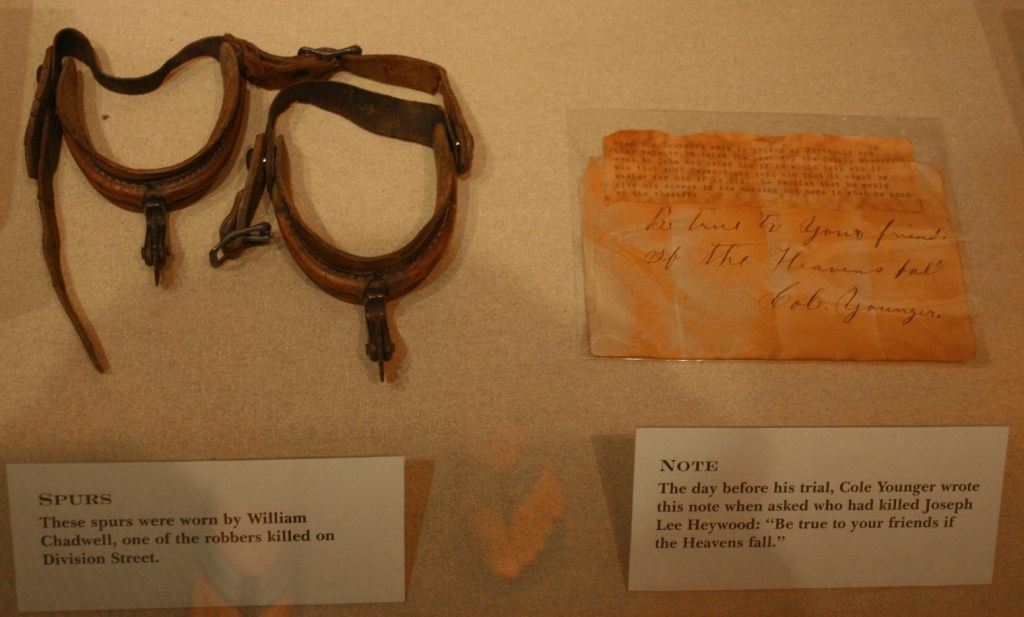

These two items in a display case caught my attention. On the right is a note written by Cole Younger the day before his trial. When asked who killed Joseph Lee Heywood, he answered. “Be true to your friends if the Heavens fall.” In other words, he wasn’t telling. To the left are spurs worn by outlaw William Chadwell, who was shot and killed on Division Street during the raid.

However, here are some select pieces of information presented by Hakala which I find particularly interesting:

- Jesse and Frank James’ father was a Baptist minister.

- The James-Younger Gang invented the “stick ’em up” bank hold-up, conducting the first bank raid during daylight business hours, in which no war was going on, in Northfield.

- One theory surmises that the James-Younger Gang was trying to get back at the Union by robbing banks.

- In following with that anti-Union theory, Hakala notes that Union General and post Civil War provisional governor of Mississippi Adelbert Ames was a member of the Northfield family—coincidentally Jesse Ames and sons—which owned the local Ames (flour) Mill. Adelbert’s father-in-law was Benjamin Butler, a Union general much-despised by Southerners. This could explain why the gang targeted Northfield since the Ames’ family had money in the First National Bank.

- While there was $15,000 in the Northfield bank vault, the outlaws made off with only $26.70 in cash, and not from the vault, which was protected by hero/cashier Heywood.

- The unarmed Heywood was shot out of frustration and “cold-blooded meanness” (Hakala’s words, not mine). He was also slit across the throat, just enough to scare him, and pistol-whipped.

- Northfield townspeople were throwing cast iron skillets, tossing bricks and aiming birdshot at the trapped gang members as they tried to ride away from the narrow canyon-like street setting in Northfield.

- A posse of some 1,000 people formed to track down the gang. The three Younger brothers were shot and captured in a gun battle at Hanska Slough near Madelia. Charlie Pitts was killed there. Frank and Jesse James escaped to Missouri.

- Jesse James was killed by a friend and fellow gang member, Robert Ford, in 1882 for the reward money.

- Postcards featuring photos of the dead outlaws, Clell Miller and William Chadwell, were sold to the public after their bodies were taken to a professional photography studio in Northfield and photographed.

- It is written into a lease on an apartment across the street from the original First National Bank that re-enactors can use the apartment each year for bank raid re-enactments. An actor is stationed in the upper level room to portray medical student Henry Wheeler shooting, and killing, Clell Miller.

Another shot of the James-Younger Gang re-enactors riding in The Defeat of Jesse James Days parade several years ago.

If you wish to witness the seven-minute bank raid re-enactment, this is the week to do so. Performers will shrug into their long linen dusters, tuck their sidearms in place, saddle up and shoot it out at the Northfield Historical Society Bank Site & Museum, 408 Division Street in downtown Northfield.

Re-enactments are set for 6 and 7 p.m. Friday, September 7—the actual date of the robbery—and at 11 a.m. and 1, 3 and 5 p.m. on Saturday and at 11 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. on Sunday.

A copy of a wanted poster posted next to the front door of the museum.

For a complete listing of The Defeat of Jesse James Days activities, click here.

For more information about the bank site and museum, click here.

The front of the museum. If you look underneath the white steps, you’ll find three holes ringed in black, supposedly bullet holes made during the raid. It’s conjecture with nothing proven, according to Christian Hakala, who has his doubts about the holes being made by bullets. That’s Division Street on the left.

The original Ames Mill, once owned by Jesse Ames and sons, and today owned by Malt-O-Meal. It’s located around the corner and across the river from the bank. The company’s hot cereal is made here in the old flour mill.

© Copyright 2012 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments