I RECENTLY FOUND LINDA NORLANDER’S fourth book—Death of a Fox—in the new fiction section of my local library. Labeled #4 in “A Cabin by the Lake Mystery,” the series name and cover art drew me to pull the book from the shelf and read the back cover summary. I do, indeed, judge a book by its cover and title. Take note, book editors and marketing teams.

Given the series name, I expected this book might be by a Minnesotan or set in Minnesota. It’s both. Sort of. The author grew up in Minnesota as the daughter of a rural newspaper editor, raised her family on 10 acres of land in the central part of our state and then moved to Tacoma, Washington. I won’t hold that against her because, well, Minnesota winters are not for everyone forever. But Norlander’s cabin mysteries are for anyone who likes a good mystery set in the Minnesota northwoods.

I’m a long-time fan of mysteries, dating back to the Nancy Drew mystery series of my youth. I’ll admit that I’ve had to force myself to read outside that genre. I still don’t read romance novels, although Norlander’s writing does include a bit of romance for main character Jamie Forest, a freelance editor who recently moved from her native New York City to a family lake cabin in northern Minnesota.

In that tranquil setting, Jamie attempts to reclaim her life, leaving behind a traumatizing event involving law enforcement in the Big Apple. This I learned in book #1, Death of an Editor. I’m reading the books in order and just finished the first. I couldn’t put it down. It was that good.

Good not only mystery-wise, but also because this is definitely a Minnesota-centric read. Norlander references reserved Minnesotans, hot dish (not casserole), Minnesota Nice, loons…even appropriately names a local eatery the Loonfeather Cafe.

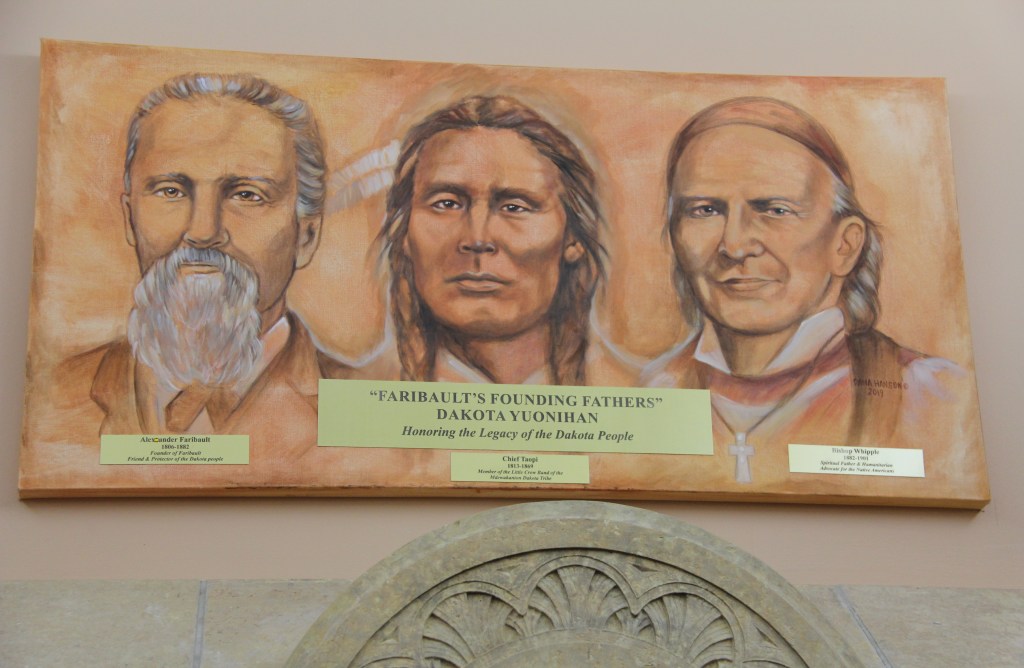

The author doesn’t shy from hard topics either, like biases against Native Americans (many of her characters are partial or full-blooded Ojibwe, including Jamie), proposed copper and nickel mining, and school shootings, all integral parts of the plot in Death of an Editor and part of Minnesota’s past and present. And, yes, an editor is murdered in this fictional book.

Jamie quickly becomes a suspect in that murder. Without revealing too much of the story, I will share that she sets out to clear her name, then that of another accused, along the way finding herself in life-death situations. There are many heart-stopping moments, questions about who can be trusted and who can’t. Lots of mysteries within the mystery to unravel.

Land greed. A troubling family past. Corrupt and threatening law enforcement officers. Men in red caps. Efforts to save the pristine northwoods from development. Secrets. Even Minnesota weather, which is forever and always a topic of conversation in our state, shape this first of Norlander’s books. Death of an Editor is set in summer and Norlander’s three subsequent books happen in our other three distinct seasons.

I just started her autumn seasonal second book, Death of a Starling, and am already drawn into the thickening plot, a continuation of book #1 as Jamie, considered an outsider and big city tree hugger, continues her efforts to uncover the truth. Already I’m finding this book to be another enthralling mystery that I can’t put down, not even to watch the 10 o’clock news.

© Copyright 2024 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments