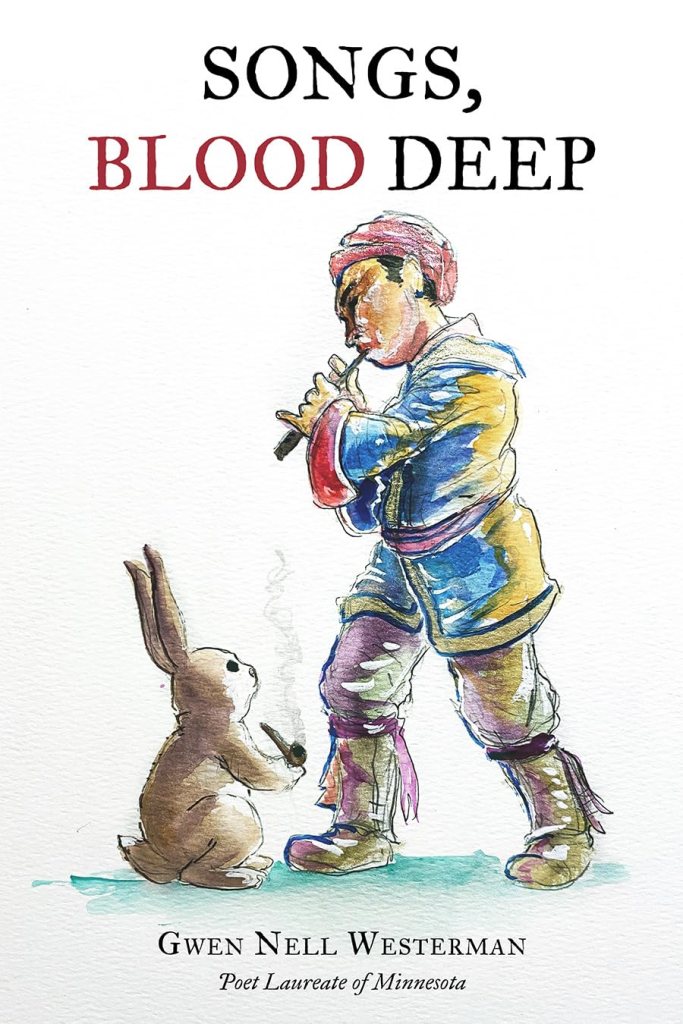

HER POEMS SING with the rhythm of a writer closely connected to land, heritage and history. She is Gwen Nell Westerman of Mankato, Minnesota poet laureate and author of Songs, Blood Deep, published by Duluth-based Holy Cow! Press.

Of Dakota and Cherokee heritage, Westerman honors her roots with poems that reflect a deep cultural appreciation for the natural world. The water. The sky. The seasons. The earth. The birds and animals. They are all there in her writing, in language that is down-to-earth descriptive. Readers can hear the birdsong, feel the breeze, see the morning light… That she pens nature poems mostly about the land of my heart—fields and prairie—endears me even more to her poetry.

This slim volume of collected poems is divided into seasons of the year, each chapter title written in the Dakota language. The book features multiple languages—Dakota, Cherokee, Spanish and English. That adds to its depth, showing that, no matter the language we speak, write or read, we are valued.

Westerman clearly values her Native heritage, how lessons and stories have been passed to her through generations of women, especially. Songs, blood deep. In her poem “First Song,” she shares a lesson her grandmother taught her about the importance of sharing. After reading that thought-provoking poem, I considered how much better this world would be if we all focused on the singular act of sharing.

This poet, who is also a gifted textile artist (creator of quilts), wraps us in her words. In the season of waniyetu, her poetry turns more reflective and introspective, as one would expect in winter. She writes of family, injustices and more. “Song for the Generations: December 26” is particularly moving as that date in history references the mass execution of 38 Dakota sentenced to death in 1862 and hung in Mankato. Westerman writes of rising and remembering, of singing and prayer. It’s a truly honorable poem that sings of sorrow and strength.

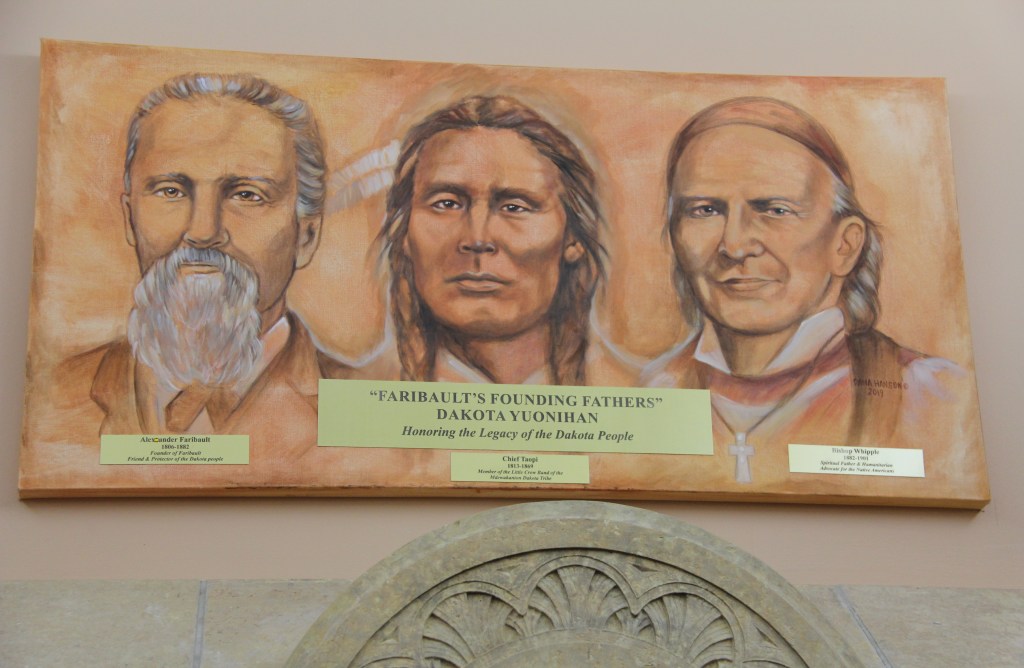

Her poems remind us that this land of which she writes was home first to Indigenous Peoples. Westerman writes of a state park in New Ulm, the sacred Jeffers Petroglyphs and Fort Snelling, where Dakota were imprisoned after the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 and before their exile from Minnesota. The name of our state traces to Mni Sota Makoce, Dakota for “the land where the water reflects the sky.” It’s included in Westerman’s poetry.

I appreciate poems that counter the one-sided history I was taught. I appreciate Westerman’s style of writing that is gentle, yet strong, in spirit. Truthful in a way that feels forgiving and healing.

In the all of these poems, I read refrains of gratitude for the natural world, gratitude for heritage and gratitude for this place we share. We sang. We sing. Songs, blood deep.

FYI: Songs, Blood Deep, is a nominee for the 2024 Minnesota Book Award in poetry. The winner will be announced May 7. This is Westerman’s second poetry book. Her first: Follow the Blackbirds. In addition to writing poetry and creating quilts, Westerman teaches English, Humanities and Creative Writing at Minnesota State University, Mankato.

© Copyright 2024 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments