FORGIVE EVERYONE EVERYTHING.

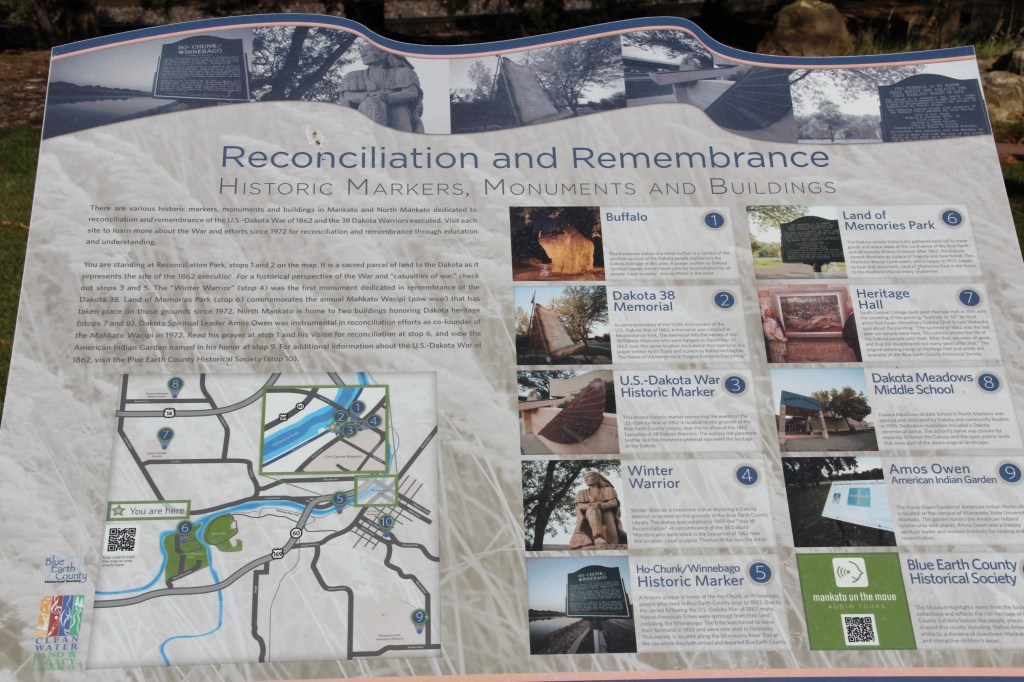

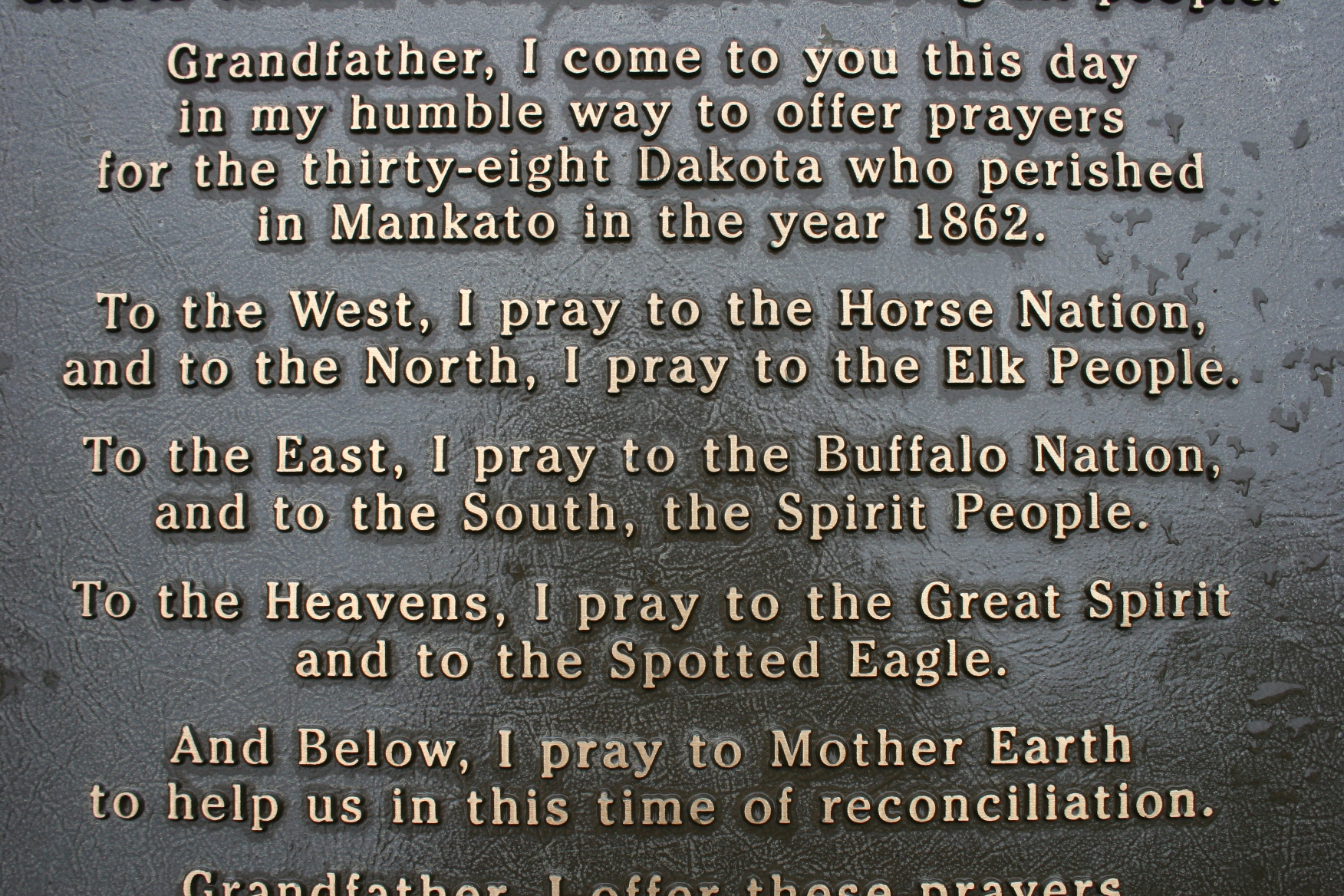

Those uppercase engraved block words, white against red on a stone bench at the Dakota 38 Memorial in the heart of downtown Mankato at Reconciliation Park, hold the strength of a people who really have no reason to forgive. But they choose to do so. And in forgiveness comes healing.

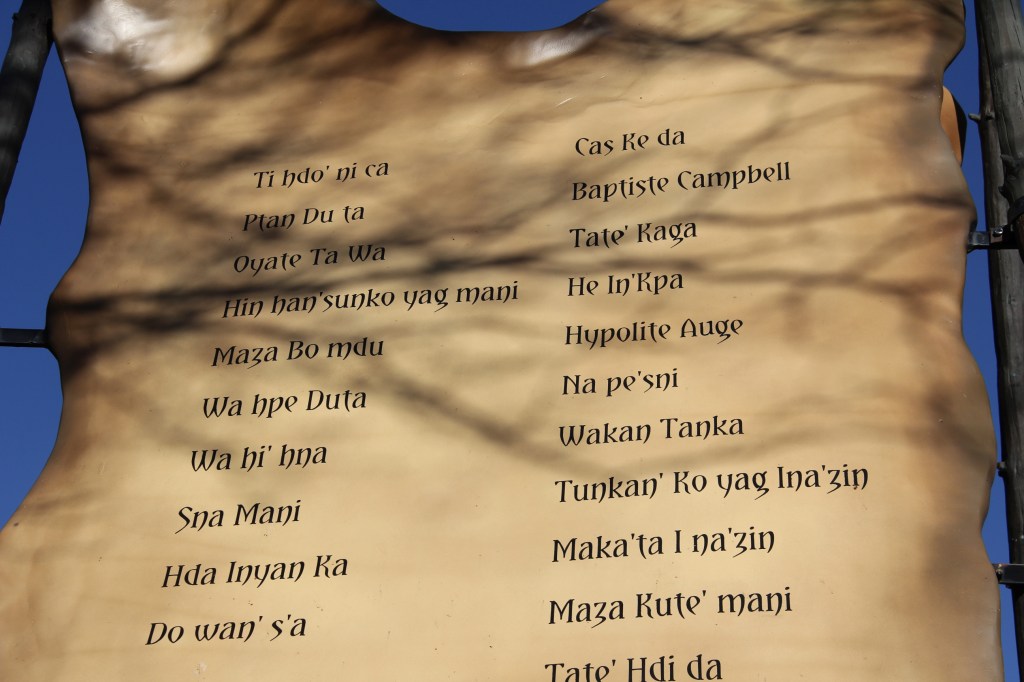

December 26 marks the date in 1862 when 38 Dakota men were hung near this site along the Minnesota River in America’s largest mass execution. Originally, 303 Dakota were sentenced to death following “trials” (the quotes are intentional) after the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. President Abraham Lincoln reviewed the list of those sentenced to death, approving the hanging of thirty-eight. Thousands gathered to watch the execution on the day after Christmas 162 years ago.

This history I learned early on, but only from a White perspective and only because of my roots in southwestern Minnesota, at the epicenter of the war. I expect many Americans, including many Minnesotans, to this day know nothing of this conflict that killed hundreds of Whites and Dakota. Internment and exile of the Dakota followed. Native Peoples suffered because of the atrocities before and after the war.

This is history I’d encourage everyone to study. And not just from a one-sided perspective. I won’t pretend that I am fully-informed. I’m not. I do, though, have a much better understanding than I did growing up. I’ve read, listened, learned. I know of stolen land, broken treaties and promises. Starvation. Injustices. Demeaning words like those attributed to a trader who told starving Dakota to “eat grass.” Andrew Myrick was later reportedly found dead, his mouth stuffed with grass.

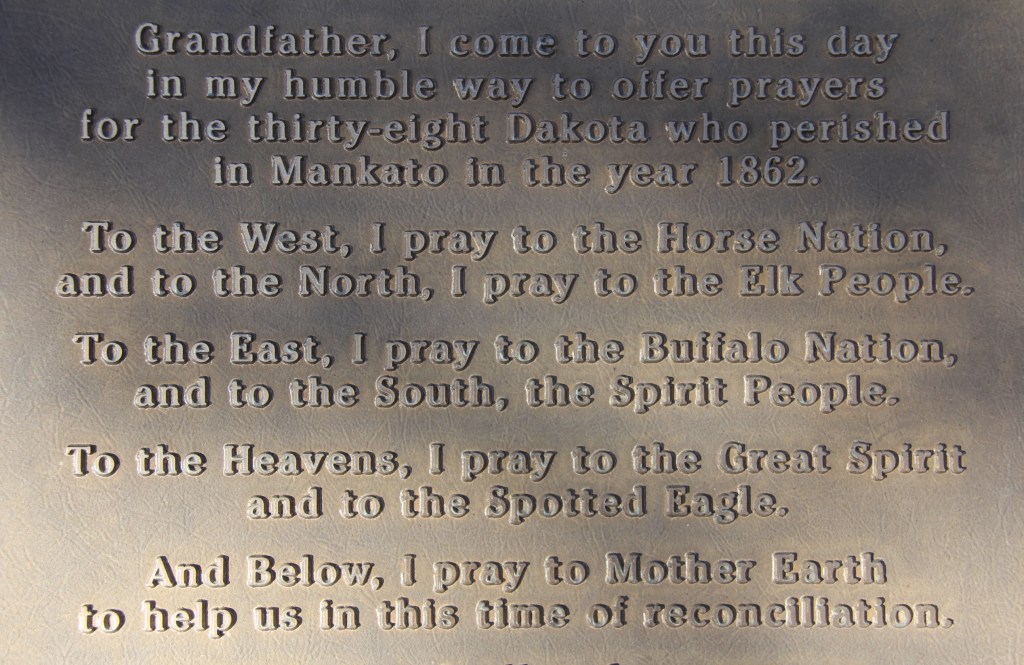

But back to those three words on that stone bench in Mankato: FORGIVE EVERYONE EVERYTHING. The Dakota truly have no reason to forgive. But they choose to do so. I’ve learned that forgiveness is part of Dakota culture and beliefs.

In the month of December, the attitude of forgiveness extends beyond words in stone to an annual horseback ride honoring the 38+2 (two more Dakota were sentenced to death two years later). This year, two rides—The Makatoh Reconciliation & Healing Horse Ride and The Dakota Exile Ride, the first originating in South Dakota, the other in Nebraska—will end on December 26 with gatherings at Reconciliation Park and the Blue Earth County Library, located across from each other.

These rides focus on educating, remembering, honoring, healing and forgiving. Five powerful verbs when connected with the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

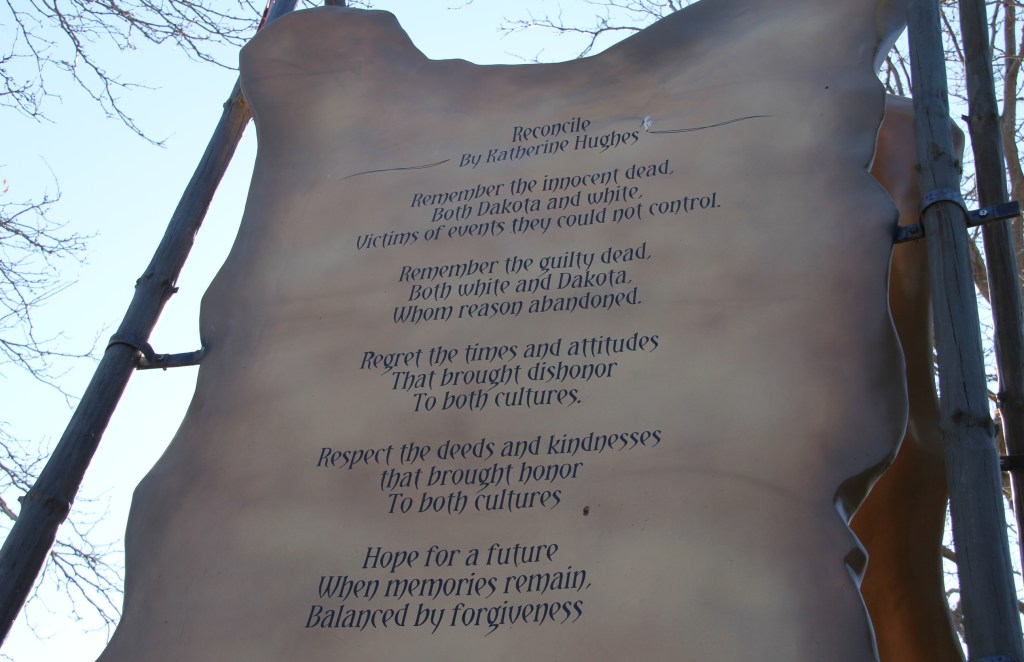

The poem “Reconcile,” written by Katherine Hughes and posted in Reconciliation Park, closes with this powerful verse: Hope for a future/When memories remain/Balanced by forgiveness.

FORGIVE EVERYONE EVERYTHING.

#

FYI: Here’s the schedule for the December 26 events. A community gathering is set for 9 am-10 am at Reconciliation Park and the library. Horseback riders arrive at 10 a.m. A ceremony in the park takes place from 10 am-11:30 am. From 11:30 am-1 pm, a healing circle will happen at the library with discussion surrounding the events of December 26, 1862, covering the past, present and future. A community meal for the horseback riders, who rode hundreds of miles to Mankato, follows.

© Copyright 2024 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments