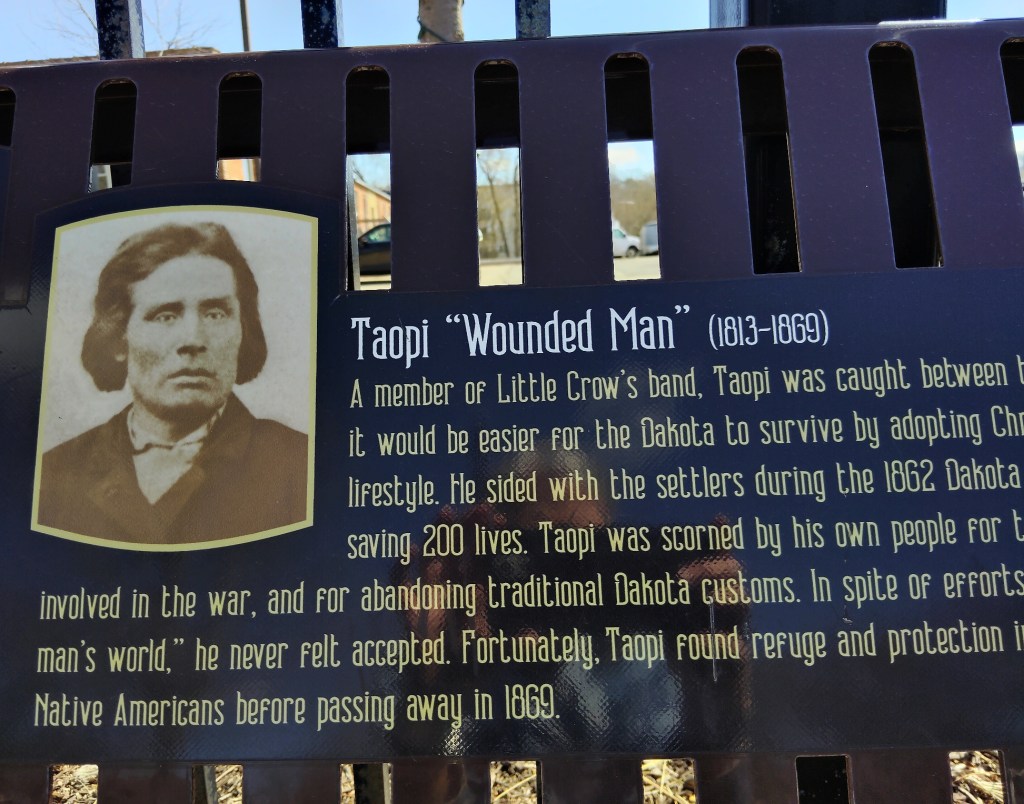

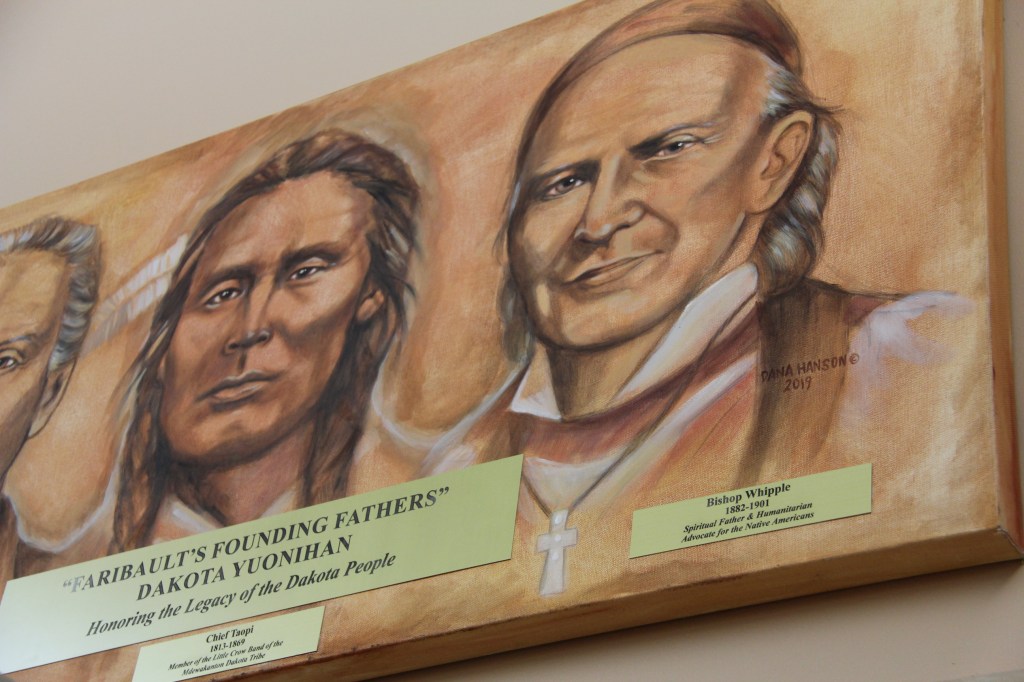

HE FOUND HIMSELF AT ODDS with his own people. A “Farmer Indian” among “Blanket Indians.” A peace promoter among those who favored war. He was Chief Taopi, a member of the Little Crow Band of the Mdewakanton Dakota. He’s buried in Faribault, at Maple Lawn Cemetery.

Recently, I attended a presentation about Taopi by Rice County Historical Society Executive Director Dave Nichols. It’s not the first time I’ve listened to local talks on the history of Native Americans in Minnesota, focused on those who called Faribault home. Each time I learn something new.

During his talk, Nichols called Taopi “a poster child for what an assimilated Dakota looks like.” And he didn’t mean that in a negative way. “You either assimilated or you would be destroyed,” Nichols said, qualifying that he wasn’t saying assimilation was right. Understood.

As settlers moved into Minnesota, pushing onto Native lands, the Dakota found themselves facing many challenges. Some, like Taopi, gave up their culture and adopted European ways, believing that was the only way to survive. That included learning to farm as the White man farmed. Taopi was considered the leader of the “Farmer Indians,” a term assigned during the U.S. Census. Dakota who continued in traditional cultural ways were labeled “Blanket Indians.”

Taopi farmed and established a school and mission, Hazelwood Republic, with chiefs Wabasha and Good Thunder on the Lower Sioux Reservation along the Minnesota River in southwestern Minnesota, Nichols shared. Because I grew up in that region, I’ve always been particularly interested in the Indigenous Peoples who were original inhabitants of the land, including Redwood and Brown counties. The region became the epicenter of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, which centered around issues of land, hunger and broken promises.

That war facilitated the banishment of most Native Americans from Minnesota. If Taopi and other Dakota would have had their way, that war may not have happened. He led the Peace Party opposed to war, while his cousin, Little Crow, led the War Party, Nichols said. Taopi protected White settlers during the short war which claimed countless lives on both sides.

Post-war, though, it mattered not to the U.S. government whether you were a Dakota person who opposed the war or who engaged in war, according to Nichols. All were considered guilty, imprisoned and eventually exiled from Minnesota (although not the Mdewakanton). Thirty-eight Dakota men were hung on December 26, 1862, in Mankato (40 miles from my community) during the largest mass execution ever in the U.S. It’s truly a tragic event in Minnesota history. But what multiples the awfulness is that 1,600 Dakota prisoners were marched to Mankato to watch the hangings before being marched back to Fort Snelling. That was new information I had not previously heard and it troubles me greatly.

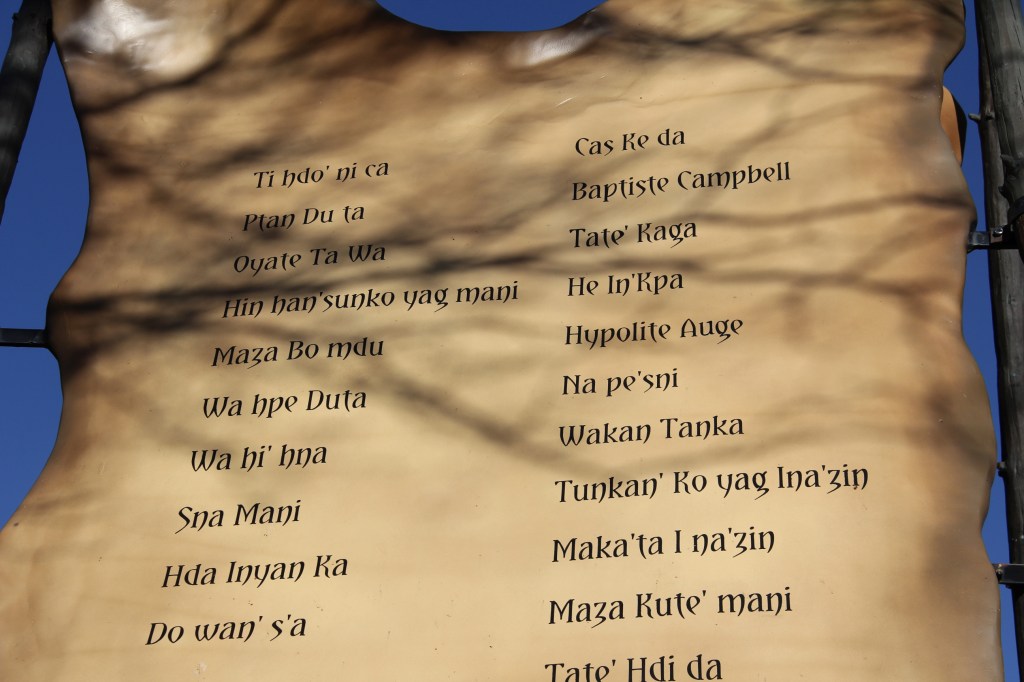

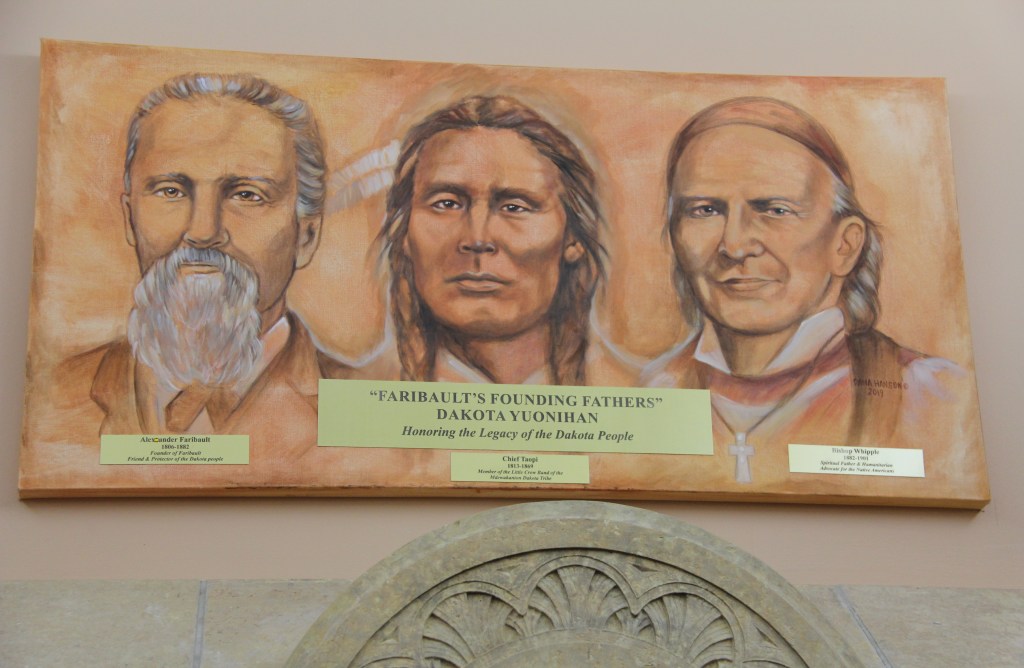

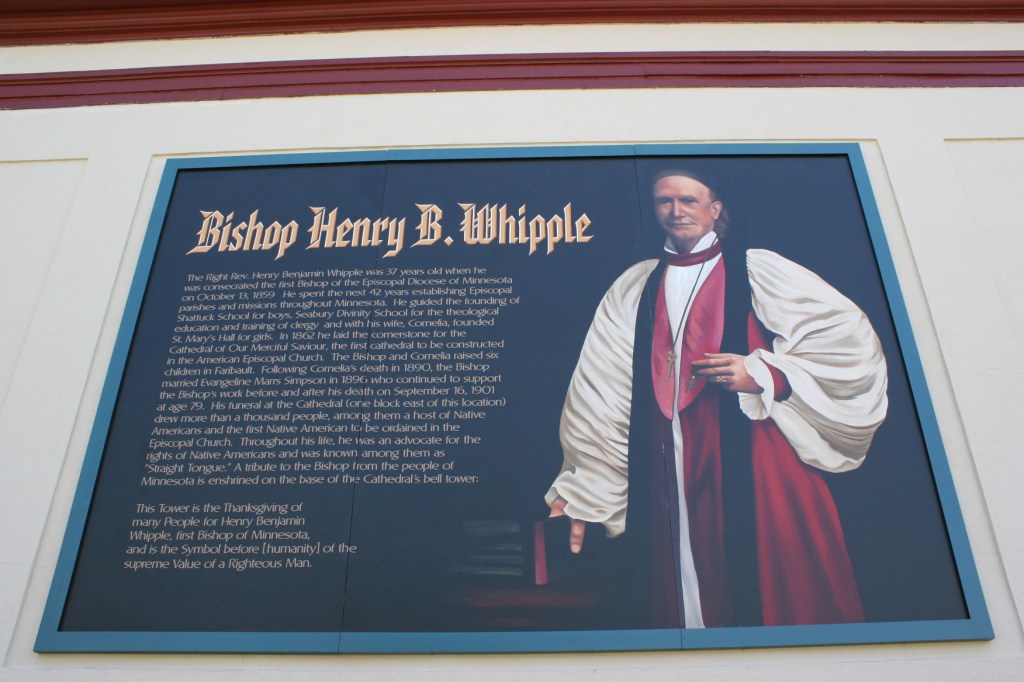

Taopi avoided prosecution and banishment, eventually landing in Faribault with 180 other Mdewakanton. About 80 were family members, according to Nichols. It was his friendship with Bishop Henry Whipple, who had long worked with and advocated for Native Peoples, that brought Taopi here. Town founder Alexander Faribault housed “the Peacefuls,” as the 180 were considered, on his land. They lived in tipis and lodges.

As you might rightly guess, not everyone in Faribault liked the Mdewakanton living among them. A wall was built in the area around Alexander Faribault’s house to protect them. Taopi became a community leader, said Nichols. As such he represented his people and mediated when necessary.

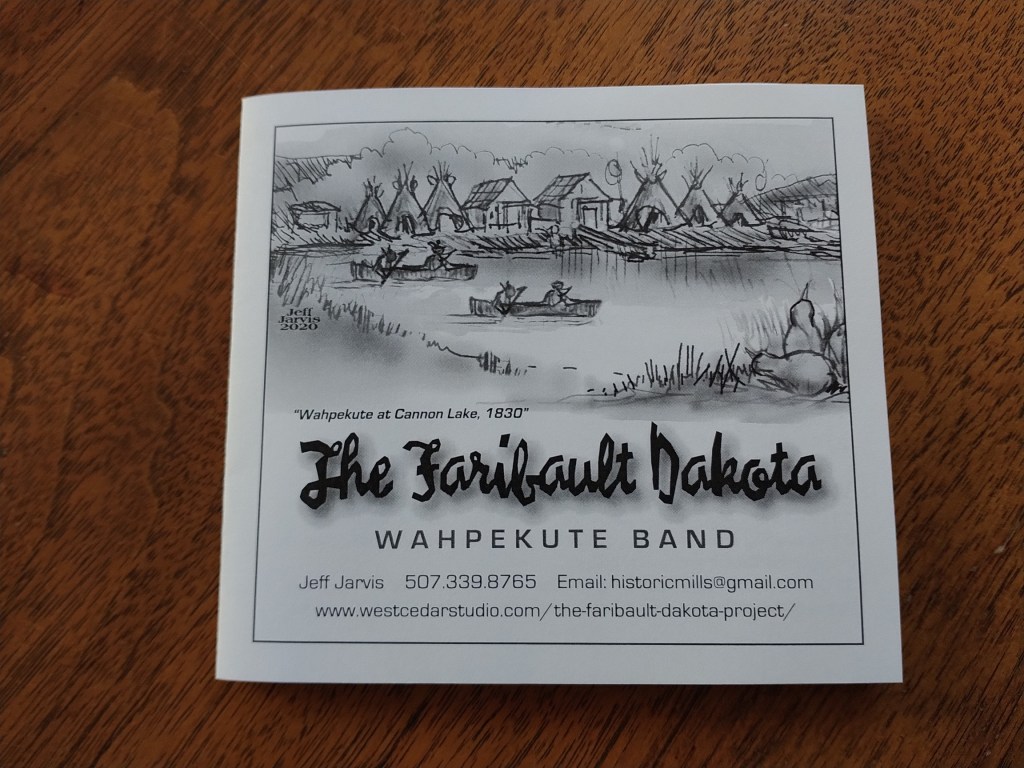

By the time of Taopi’s 1869 death, 90 of the 180 Mdewakanton who settled in Faribault had already left. But they left behind an imprint upon the land, not necessarily seen or appreciated even today. Yet, efforts are underway to change that with The Faribault Dakota Project. Nichols couldn’t speak specifically to that, only to say that local historian Jeff Jarvis has been working with the Dakota community on how to memorialize and honor the Indigenous Peoples of Faribault. That also includes the Wahpekute Dakota.

Among the locales discussed by those attending Nichols’ talk was Peace Park, a triangle-shaped slice of property near Buckham Memorial Library. Alexander Faribault donated the land to the city with the stipulation that it never be developed. According to Nichols, the park is a protected burial site, where at least two Dakota are buried. Their bones were unintentionally uncovered in 1874 and then reburied. Today nothing marks that land as a cemetery. Rather a faith-based WWII monument stands in Peace Park. There is no reference to the Dakota. Perhaps some day this will be righted and the land publicly recognized as sacred ground. That is my hope as I continue to learn about the Dakota who once called Faribault home. I am grateful for every opportunity to grow my knowledge of them and their importance in local and state history.

#

FYI: Here are some suggested Dakota-connected places to visit in Faribault: the Rice County Historical Society Museum, Maple Lawn and Calvary cemeteries, the Cathedral of Our Merciful Saviour, a mural on the Central Park Bandshell and information on an historic-themed bench along Central Avenue.

Two fun facts: A small southeastern Minnesota town in Mower County near the Iowa border is called Taopi, named after the Mdewakanton Dakota chief. It suffered a devastating tornado in April 2022. The town celebrates its 150th birthday this year.

A woman attending Dave Nichols’ talk named her horse Taopi after Chief Taopi.

© Copyright 2025 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments