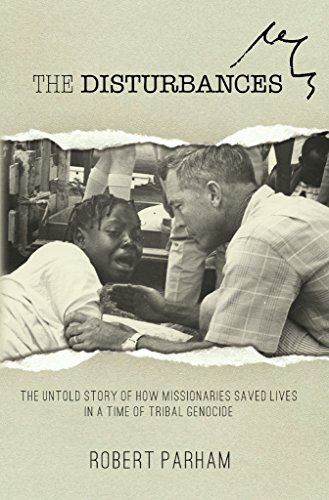

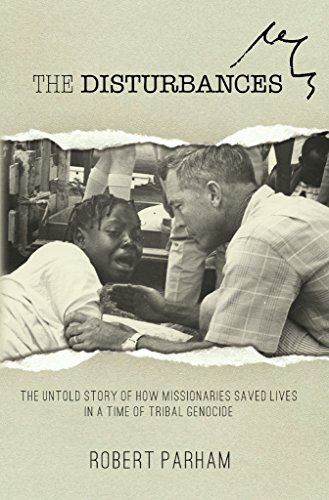

The Disturbances is told in both book and film.

I NEVER EXPECTED to find myself on the verge of crying while watching a documentary about a civil war in Nigeria in 1966. But I did on Sunday afternoon as I viewed The Disturbances at Redeemer Lutheran Church in Owatonna.

Produced by the Baptist Center for Ethics, the film tells the stories of missionaries and their families who, caught in the middle of a civil war, helped save the lives of Igbos, a tribe victimized by genocide. Thousands upon thousands of tribal natives died, many hacked to death by machetes.

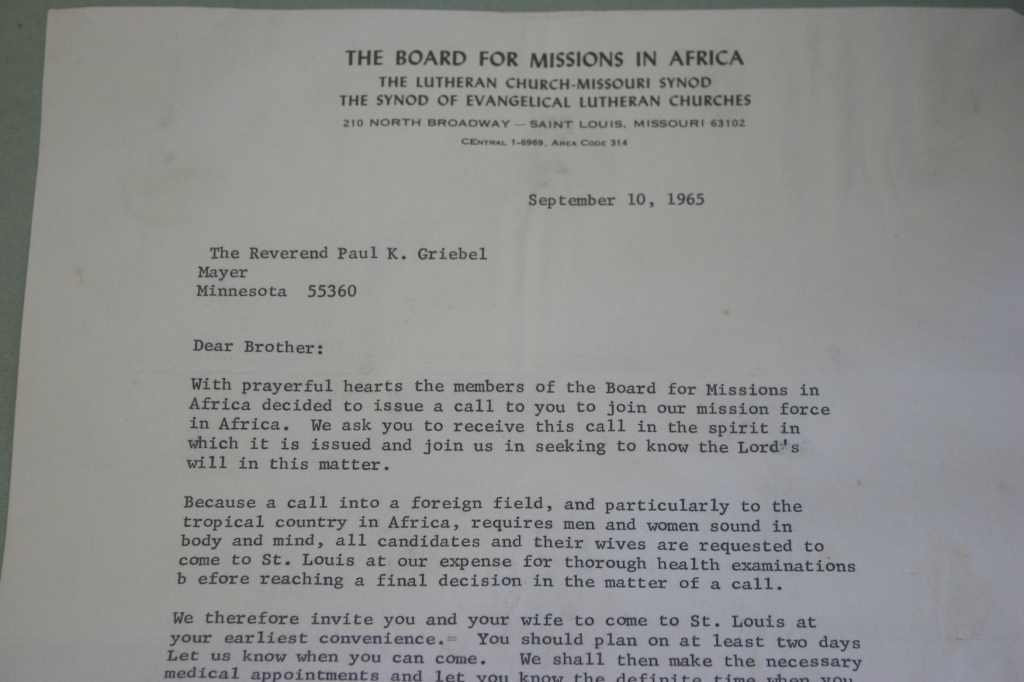

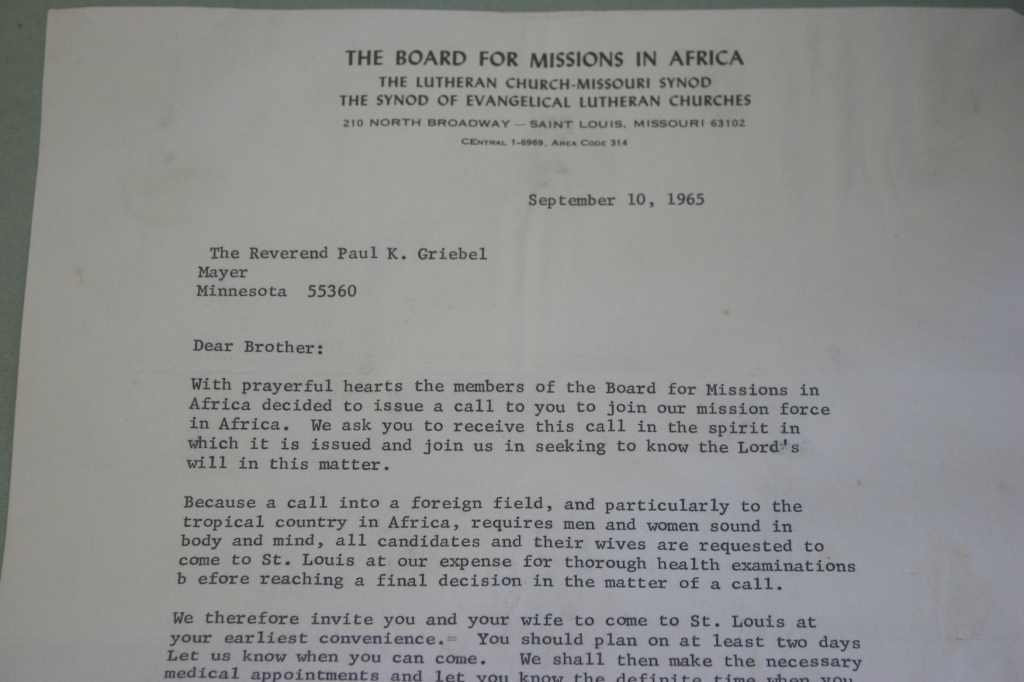

The letter calling the Rev. Paul Griebel and his family to the African mission field.

I’ll admit, I’m not the best with history and geography and, until recently, knew nothing of this strife in Nigeria 51 years ago. But then my pastor-friend, the Rev. Kirk Griebel of Redeemer, alerted me to the documentary. He was an “MK,” as missionary kids were tagged, living in Nigeria with his Lutheran Church Missouri Synod pastor father, mother and five siblings at the height of the violence. He was only eight when his family arrived from Minnesota, thus recalls little.

But plenty of others do remember the civil war and spoke openly about it for the first time in The Disturbances, the film titled after the code name the missionaries gave to the conflict. Their experiences were horrible. And memorable. Even 50 years later, their words and faces reveal the trauma of witnessing such violence.

Artist Susan Griebel crafted this quilted art from fabric her mother-in-law, Margaret Griebel, acquired in Africa.

The featured missionaries (including pastors, teachers and others from many denominations) lived in and around the city of Jos, a cultural melting pot and the epicenter of the violence. They were warned, “Tomorrow there will be trouble.” The next day the phone rang followed by a three-word declaration: “It has started.”

A beautiful carving from Africa, among those the Rev. Paul and Margaret Griebel brought back to the U.S. from Africa.

And so the stories emerged of Igbos hiding in fields and in rafters of the church sanctuary and in a store room. Stories of Igbos escaping with the help of missionaries. Stories of missionaries hiding a body in elephant grass. Stories of murdered Igbos picked up by trash trucks and buried in mass graves. Stories of the teen children of missionaries tending the wounded inside a police compound. Stories of missionaries lighting a runway with the headlights of their cars during an evacuation effort.

As I listened, I felt my grief rising, heightened perhaps by the unsettling current events in our own country regarding refugees. I wonder what stories they might tell, what violence many have fled/desire to flee for safety in America.

Two stories in particular imprinted upon me from The Disturbances. A victim of the attacks asked a young woman tending him whether she would be his daughter. His entire family had been slaughtered. She agreed, reciting Psalm 23 (The Lord is my shepherd…) and The Lord’s Prayer to the dying man. The woman, 50 years later, still remembers his final words. “I’m going home, my daughter.”

Missionary children at ELM House (Evangelical Lutheran Mission House) in Nigeria with teacher Carl Eisman in the back row. Missionary children lived in the hostel so they could attend boarding school in Jos. The Rev. Paul and Margaret Griebel served as houseparents. Three of their children, including Kirk, are pictured in this group photo. Photo courtesy of the Rev. Kirk Griebel.

And then there’s the story shared by Carl Eisman, a Lutheran teacher at Hillcrest School (a boarding school in Jos) and friend/co-worker of the Rev. Paul Griebel. After evacuating children from a hostel, the two men remained hidden there with tribal members. As an angry mob approached ELM House, Eisman hid in the shadows with a hunting knife. And, as he recounted, Rev. Griebel sat at a nearby table reading Scripture and praying. Eventually, the mob dispersed and the men emerged to find a body, one they temporarily hid in elephant grass.

My friend, the Rev. Kirk Griebel, doesn’t recall his father (or mother; both now deceased) ever talking about the violence they witnessed. He remembers only an angry mob and waiting outside a fenced police compound where the injured and dying were taken.

This close-up of Susan Griebel’s Nigerian-themed art shows the dove she incorporated as representing the Holy Spirit. In the film, one interviewee said the missionaries had only one resource–that of prayer.

The film explains why the missionaries didn’t speak openly about the violence, even to family and church staff back home. They felt caught without resources in the middle of a civil war. As foreigners, they thought it best to lie low. They desired, too, to protect the children, to normalize their lives. And so they remained mostly silent. Until now and the documenting of their experiences in The Disturbances.

Given the time period and their foreigner status, I understand the guarded position. Missionaries and Nigerian pastors met, though, for two days in October 1966 to discuss “the disturbances” privately. I am thankful that these long-ago missionaries and their family members have now chosen to speak publicly about their experiences. For it is through the telling of personal stories that we learn and begin to understand suffering, courage, compassion and faith in times of violence. And for those who witnessed such atrocities, talking begins the process of healing.

FYI: Upcoming screenings of The Disturbances are scheduled in Missouri and Alabama. Click here for details. The Rev. Kirk Griebel will present the film this Wednesday, February 1, at 6 p.m. at King of Kings Lutheran Church, 1701 NE 96th St. in Kansas City, Missouri.

© Copyright 2017 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments