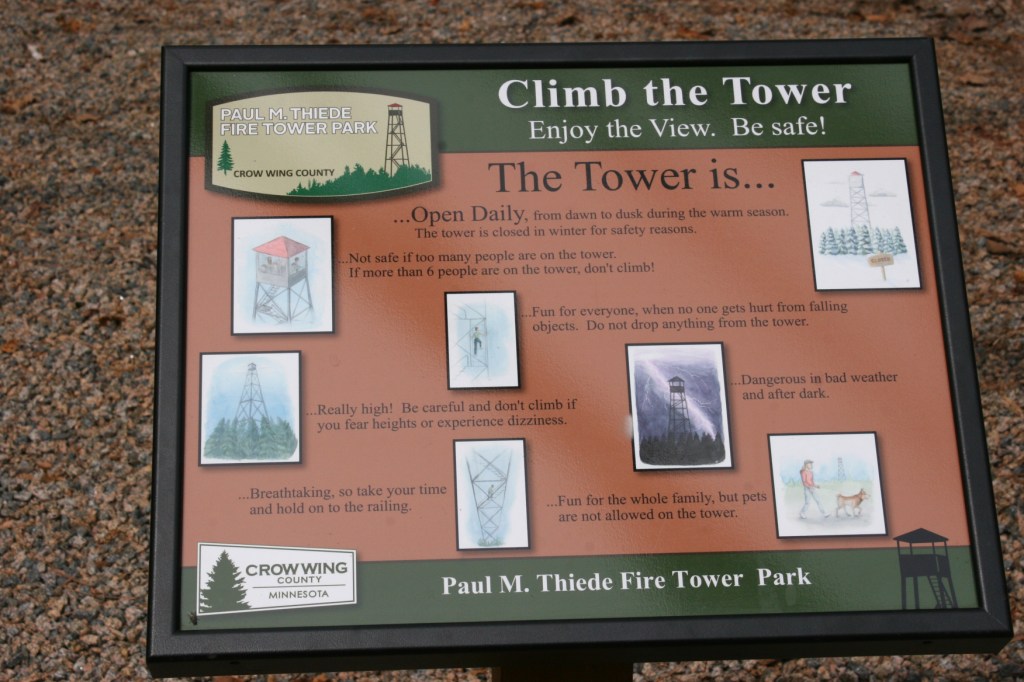

Really high! Be careful and don’t climb if you fear heights or experience dizziness.

I heeded the warning and stayed put. Feet on the ground. Camera aimed skyward. Toward the 100-foot high Paul M. Thiede Fire Tower just outside Pequot Lakes in the central Minnesota lakes region. The top of the tower pokes through the trees, barely visible from State Highway 371. Turn off that arterial road onto Crow Wing County Road 11, turn left, and you’ve reached the fire tower park.

The Paul M. Thiede Fire Tower Park (named after the county commissioner instrumental in developing this 40-acre park) offers visitors an opportunity to hike to, and then climb, the historic tower built in 1935 by the Civilian Conservation Corps. As one who prefers low to high, I was up for the 0.3 mile hike, but not the climb.

Before Randy and I headed onto the trail, though, we read the interpretative signage featuring information on the tower (which is on the National Register of Historic Places), Minnesota wildfires and other notable fire facts. This summer marked an especially busy fire season in the northern Minnesota wilderness. Those of us living in the southern part of the state felt the effects also with smoke drifting from the north (including Canada) and from the west (California). That created hazy skies and unhealthy air some days, unlike anything I’ve ever experienced.

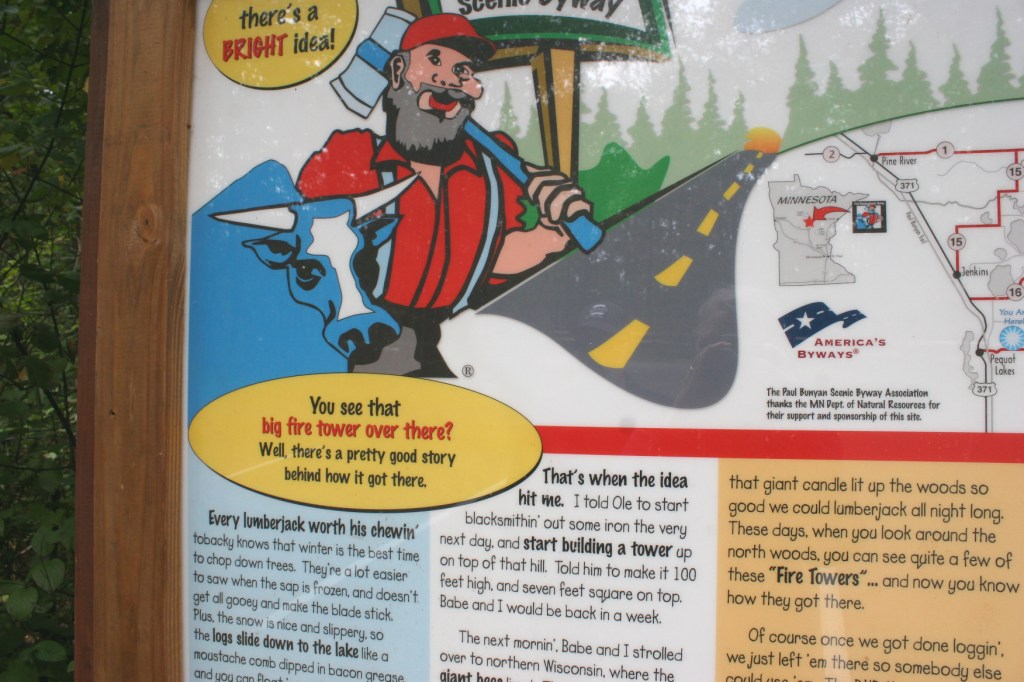

We also read a bit of Paul Bunyan lore, a fun addition to the park located in the Paul Bunyan Scenic Byway area. This region of Minnesota is big on lumberjack stories about Paul and his sidekick, Babe the Blue Ox. The Pequot Lakes water tower is even shaped like Paul’s over-sized fishing bobber.

Once we’d finished reading, and then admiring the beautiful new picnic shelter, we started off on the pea rock-covered trail through the woods and toward the tower. Up. Up. Up.

After awhile, I began to tire, to wonder, how much farther? And just as I was about to declare myself done climbing steps, Randy assured me the tower was just around the bend. Yes.

Once there, I stood at the base of the tower, reading the rules and warnings. I decided I best admire the ironwork from below. And I did. There’s a lot to be said for the 1930s workmanship of skilled craftsmen.

Randy, though, started up the layered steps leading to a seven-foot square enclosed look-out space at the top of the tower. At that height, fire watchers could see for 20 miles.

As I watched, Randy climbed. Steady at first, but soon slowing, pausing to rest. “You don’t have to go all the way to the top,” I shouted from below. He continued, to just above treetop level, and then stopped. He had reached his comfort height level.

I can only imagine how spectacular the view this time of year, in this season of autumn when the woods fire with color. We visited in mid-September, when color was just beginning to tinge trees.

Eventually, we began our retreat down the trail, much easier than ascending.

Occasionally I stopped to photograph scenery, including species of orange and yellow mushrooms. Simply stunning fungi.

We also paused to visit with a retired couple on their way to the tower. They have a generational lake home in the area, like so many who vacation here. While we chatted, a young runner passed us. I admired her stamina and figured she’d face no physical challenges climbing the 100-foot tower.

Just like a domesticated black bear that once escaped and scampered up the tower. A ranger lured him down with a bag of marshmallows. That is not the stuff of Paul Bunyan lore, but of life in the Minnesota northwoods. This historic fire tower, which once provided a jungle gym for a bear and a place to scout for wildfires, now offers a unique spot to view the surrounding woods and lakes and towns. If you don’t fear heights or experience dizziness.

FYI: The Paul M. Thiede Fire Tower is open from dawn to dusk during the warm season, meaning not during Minnesota winters. Heed the rules. And be advised that getting to the tower is a work-out.

Right now should be a really good time to catch a spectacular view of the fall colors from the fire tower.

© Copyright 2021 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments