I CAN’T IMAGINE a world without books. From the time I was first read to and then learned to read as a young child, I have loved books. From books, I’ve learned, I’ve escaped, I’ve broadened my world well beyond southern Minnesota.

From reading the writing of others, I’ve grown, too, as a writer. Laura Ingalls Wilder, in her Little House books, taught me the importance of detail, of setting, in writing. I grew up on the prairie, some 20 miles from Walnut Grove, once home to the Ingalls family. A grade school teacher read the entire Little House series to me and my classmates. Books have, in many ways, shaped me.

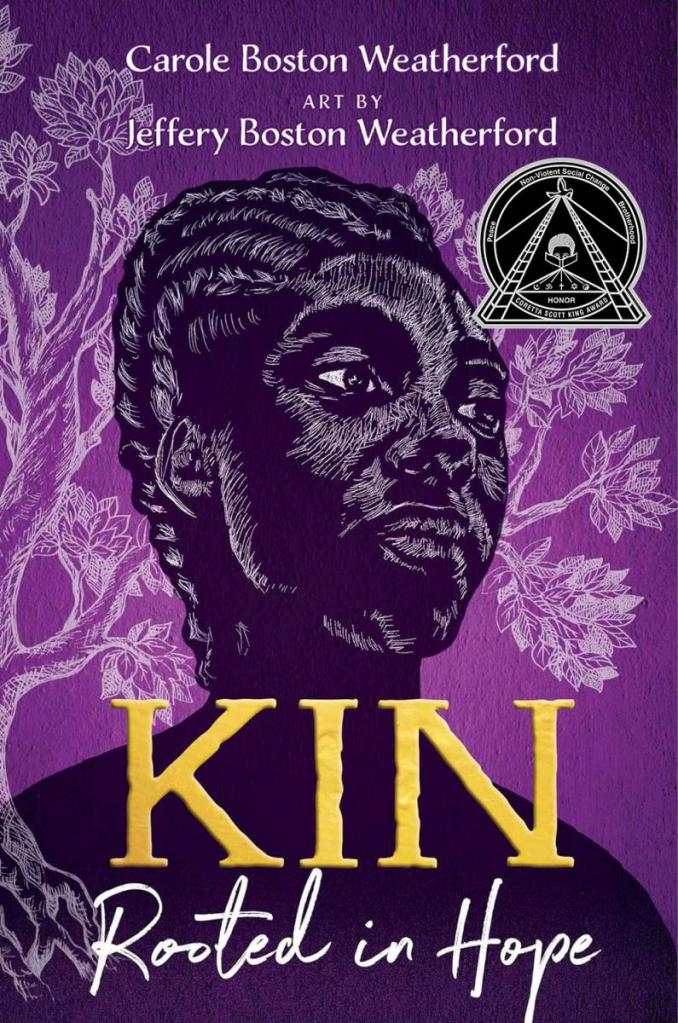

But imagine a world without books. That was a reality for slaves in America, denied access to books and to education. I just finished reading Kin: Rooted in Hope, written by Carole Boston Weatherford and illustrated by her son, Jeffery Boston Weatherford. The young adult book, published by Atheneum Books for Young Readers, was named a Coretta Scott King Author Honor Book 2024. It is a book that ought to be read by everyone not only for its insightful poetry-style storytelling, but also for its haunting scratchboard art.

Adding to the overall subliminal effect is the way in which the book is printed. Black words ink white paper. White words imprint black pages. And the artwork is made by etching away black ink to reveal white. This mixed usage of black and white, reinforces the storyline of slavery and slave owners. Black. White.

As I read Kin, which I pulled from a book display for kids and teens at my local library, I was increasingly horrified by what I read. Sure, I’ve read about slavery in history books. But this approach of historical fiction really brought home the ugliness, the abuse, the violence, the awfulness of slavery in a personal way. Fiction rooted in truth.

Children born into slavery. Whippings. An auctioneer’s gavel. Names written on an inventory list along with commodities. Jemmy. Big Jacob. Lyddia. Tom. Walter. Isaac. Mush ladled into a trough. Swimming banned lest an escape to freedom be attempted. And on and on. Atrocities that seem unfathomable to inflict upon individuals chained in Africa, sailed to Maryland, sold, abused, treated like property by wealthy white families.

But in the all of this, threads of kinship, endurance, strength and hope, even defiance, run. Perhaps my favorite line in the book is that of Prissy, a house servant waiting on a dinner guest. He leers at her, making an inappropriate comment. She wants to tell him that she spit in his soup. At this point half way into the book, I applaud her unstated rebellion. As the chapters unfold, so does the move toward freedom for slaves. The author writes of freedom at last and of current day issues (controversial statues in public places, the murder of George Floyd…), all interspersed with a whole lot of history (including historic figures like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman…).

Even though this book is written for young adults, it should be read by older adults, too, who need to hear Prissy’s defiant voice. Author Carole Boston Weatherford gives voice to those who endured slavery, and to those whose family histories trace to enslavement, including her ancestors. Her son’s detailed scratchboard art reinforces the story, the words which wrench the spirit.

Kin: Rooted in Hope proves an especially fitting read during February, Black History Month. Through this book of historical fiction, I’ve learned more about a part of U.S. history which is horrendous in every possible way. That humanity can treat humanity so atrociously seems unfathomable…until I consider underlying and outright racist attitudes which continue yet today.

© Copyright 2024 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments