He was known as “Straight Tongue” for his honesty. He was disparagingly called “The Sympathizer” by others for the compassion and care he held for the Dakota. He was Bishop Henry Whipple.

Thursday evening, Rice County Historical Society Executive Director David Nichols spoke to a packed room about this Episcopal priest who played such a pivotal role in Minnesota history, specifically during the time shortly before, and then after, The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. For me, personally, Nichols’ focused talk connected my home region of Redwood County, the area in which the war centered, to my home of 40 years, Rice County.

I grew up with a limited (white) perspective of the war with no knowledge of Whipple. I only learned of this New York born clergyman upon my move to Faribault in 1982. Nichols broadened my understanding during his presentation and during a question and answer session that followed.

HIGH TENSIONS

Whipple arrived here in 1860 as the newly-elected Bishop of Minnesota, settling in Faribault. Already at that time, tensions were mounting among settlers and the first peoples of Minnesota, Nichols said. Tensions also existed between the “Farmer Indians” (those who adapted to Euro culture) and “Blanket Indians” (who maintained their Native culture, traditions and lifestyle). Conditions on reservations were terrible with disease, starvation, and dishonest agents failing to provide promised government annuities.

That is the situation Whipple found when he landed in Minnesota. It was a time, noted Nichols, of “tensions about to boil over.” And eventually they did with the outbreak of war in August 1862. It was a decidedly bloody and awful war, as all wars are. Some 600-800 died and the Dakota were eventually displaced from their land.

THE SHAPING OF A HUMANITARIAN

To understand Whipple’s position and part in this, Nichols provided background. Whipple was involved in New York politics as a “conservative Democrat,” a term which drew laughter from the crowd at Thursday’s presentation. He briefly attended Oberlin College, notable because the college was among the earliest to admit women and African Americans. And Whipple was ordained in 1849, during the so-called “Second Great Awakening” with a focus on civil rights.

Learning this helped me better understand the bishop. All of these experiences shaped a man who spoke with honesty and compassion, advocated for Minnesota’s Indigenous Peoples (both the Dakota and the Ojibwe, natural enemies), called for reform and peace and understanding. Whipple was, said Nichols, a voice for calm, calling for justice, not vengeance, when the short-lived U.S.-Dakota War ended.

ADVOCATING FOR PARDONS

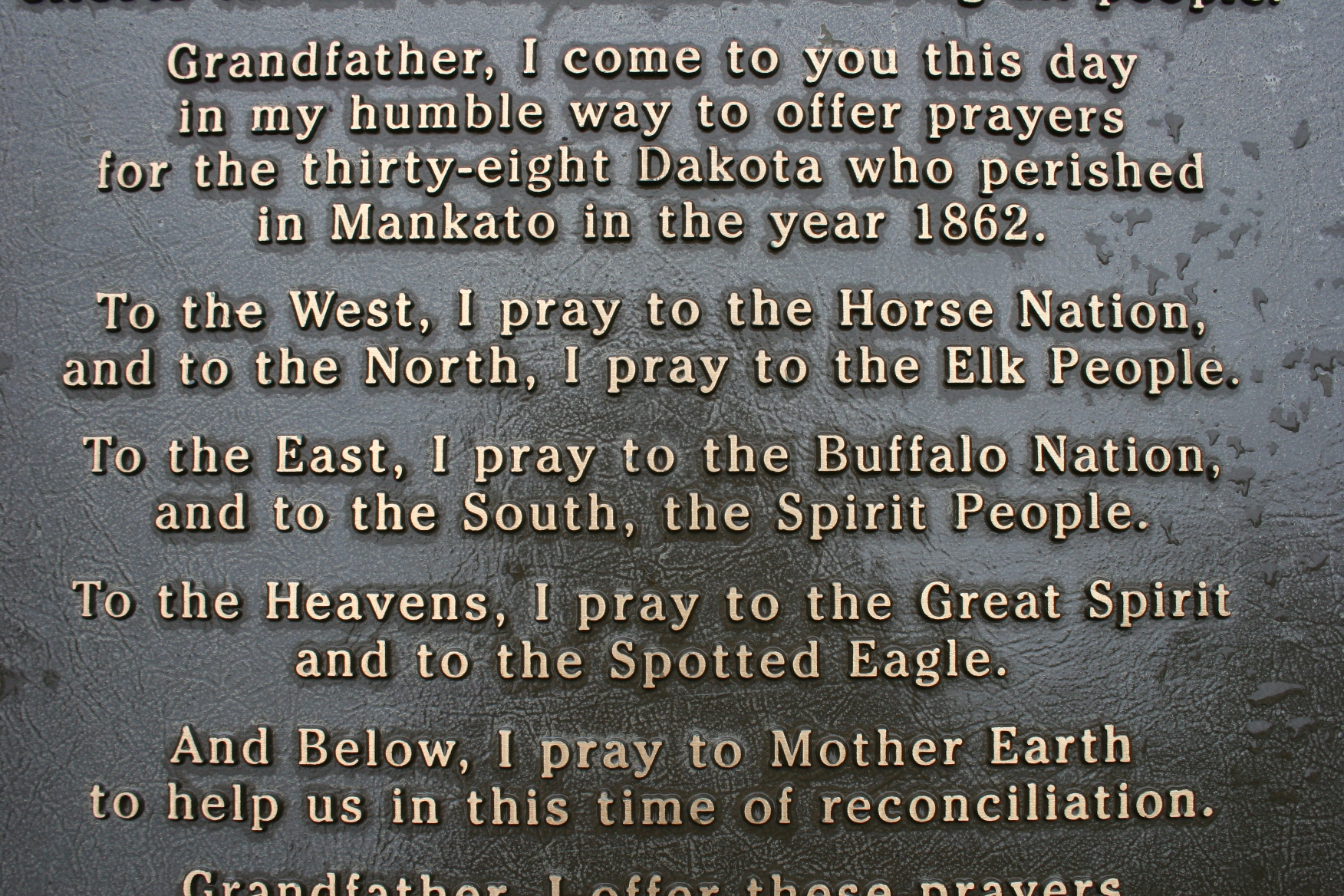

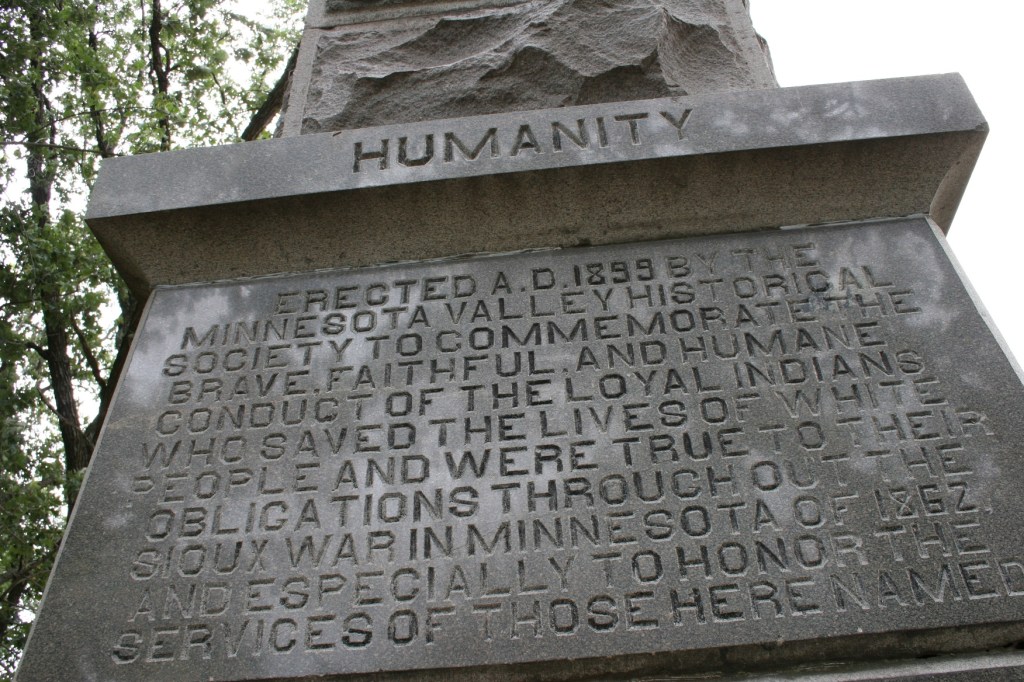

In his many years of missionary work and advocacy, even when his life was threatened by those who viewed him as an “Indian sympathizer,” one singular moment stands out to me. And that is Whipple’s efforts to save the lives of 303 Dakota men sentenced to death after the war. He met with President Abraham Lincoln and was “partly responsible,” Nichols said, for Lincoln’s eventual pardon of all but 38 Dakota. The 38, plus two others, were hung in a public mass execution in Mankato on December 26, 1862. It is a terrible and profoundly awful moment in Minnesota history, especially the history of the Dakota.

ASSIMILATION

While listening to Nichols’ presentation on Whipple, I felt conflicted. Conflicted because the bishop was, he said, “a strong assimilationist.” That label bothered me until I talked further with Nichols. He explained that Whipple did not view himself and Europeans as superior to Native Peoples, but rather observed, in the context of place and time and thinking, the need to adapt versus being driven out. That helped me better understand Whipple’s approach. I recognize, though, and acknowledge the current-day struggles with assimilation, especially as it relates to Indian boarding schools. I appreciate the recognition of, and return to, culture, tradition and heritage today.

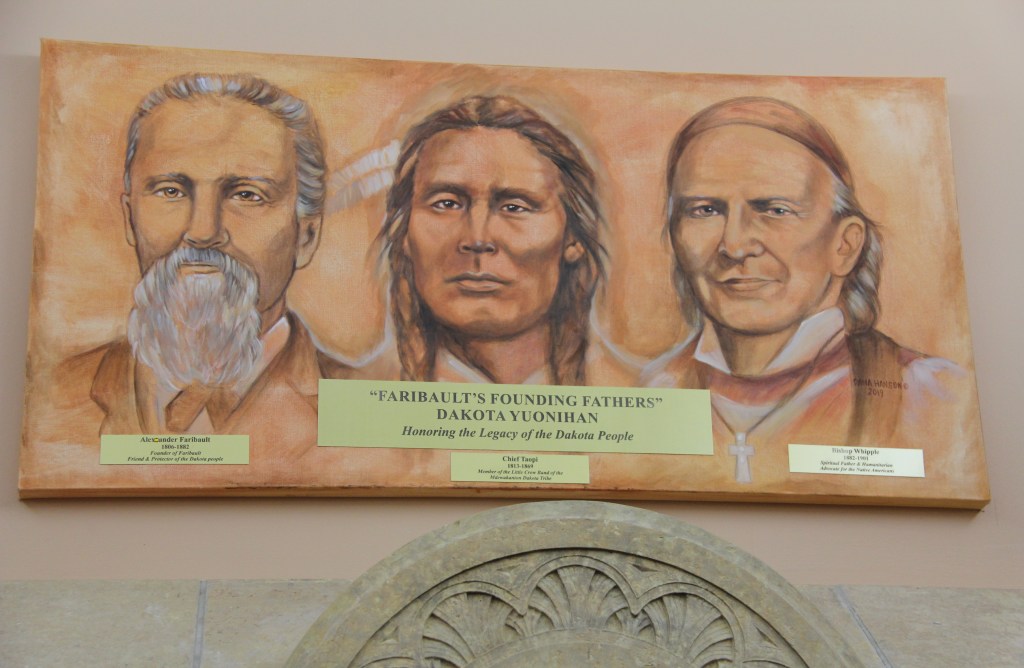

WELCOMING THE DAKOTA TO FARIBAULT, OR NOT

Whipple, by his words and actions, embraced the Dakota and Ojibwe who called Minnesota home long before white settlers arrived, long before he moved to Faribault. My community, founded by fur trader Alexander Faribault, himself half Dakota, was a safe haven for the Dakota (“you don’t attack family”) during the 1862 war and thereafter, Nichols said. Faribault and Whipple worked together to move 180 Dakota from St. Paul’s Fort Snelling, where they were held following the war, to live on land Alexander owned along the Straight River in Faribault.

I wondered, “Were they welcomed here?” The answer, given by former RCHS Executive Director Susan Garwood, was as I expected. Mixed. While some supported the Dakota’s presence in Faribault, others were vocal in their opposition. In that moment, I thought of our ever-growing immigrant population in my community. Many welcome our newest neighbors and, like Alexander Faribault and Bishop Henry Whipple, support and encourage them. But many also want them gone. History repeats.

MARKING HISTORY

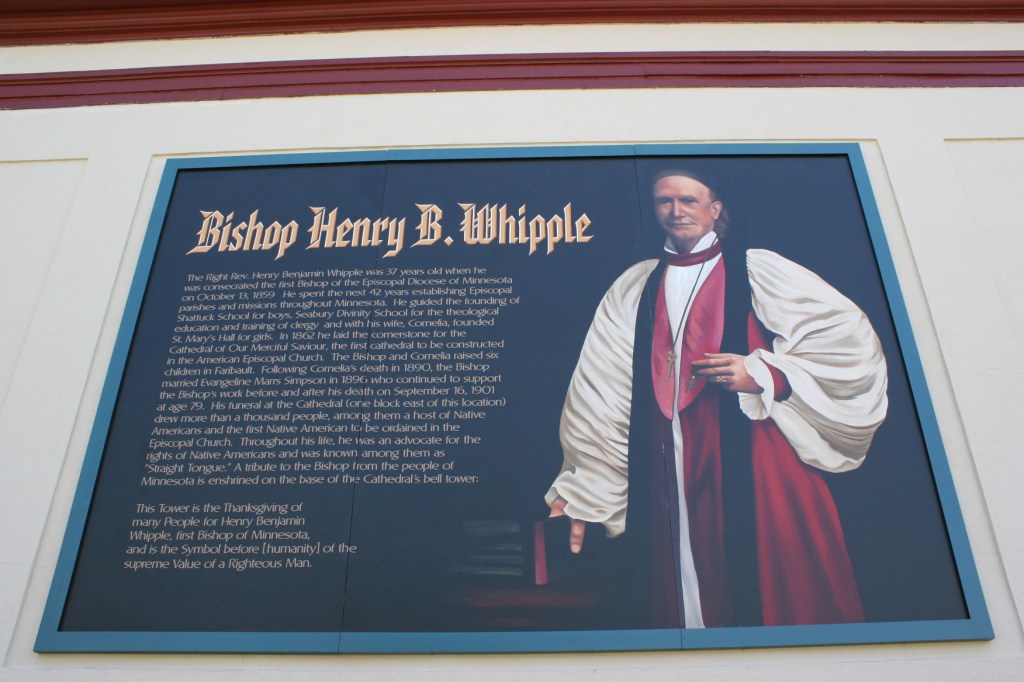

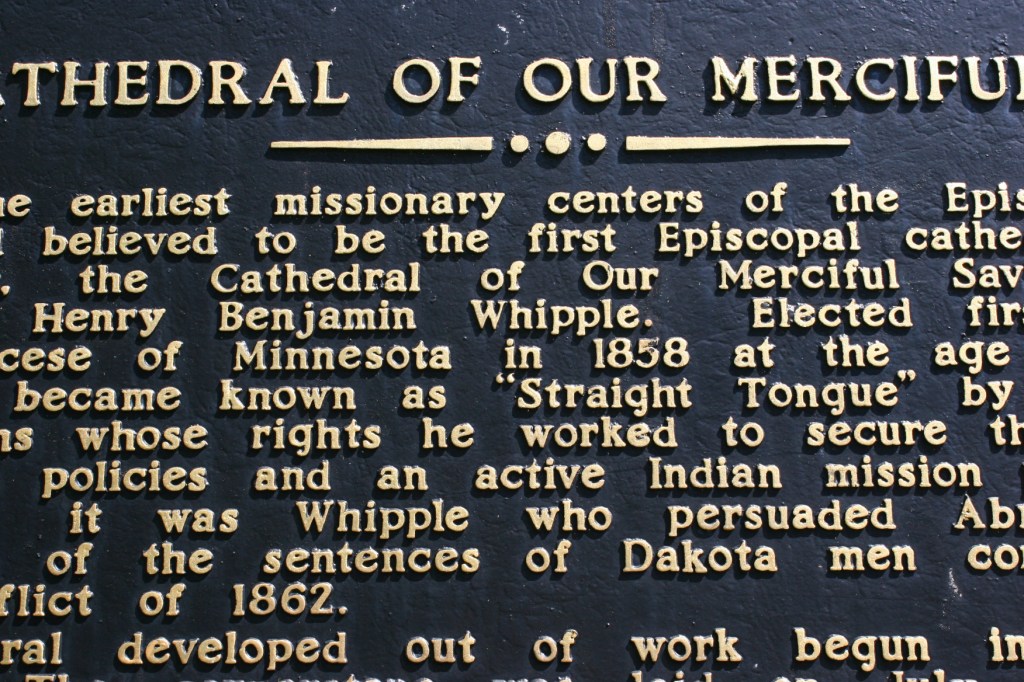

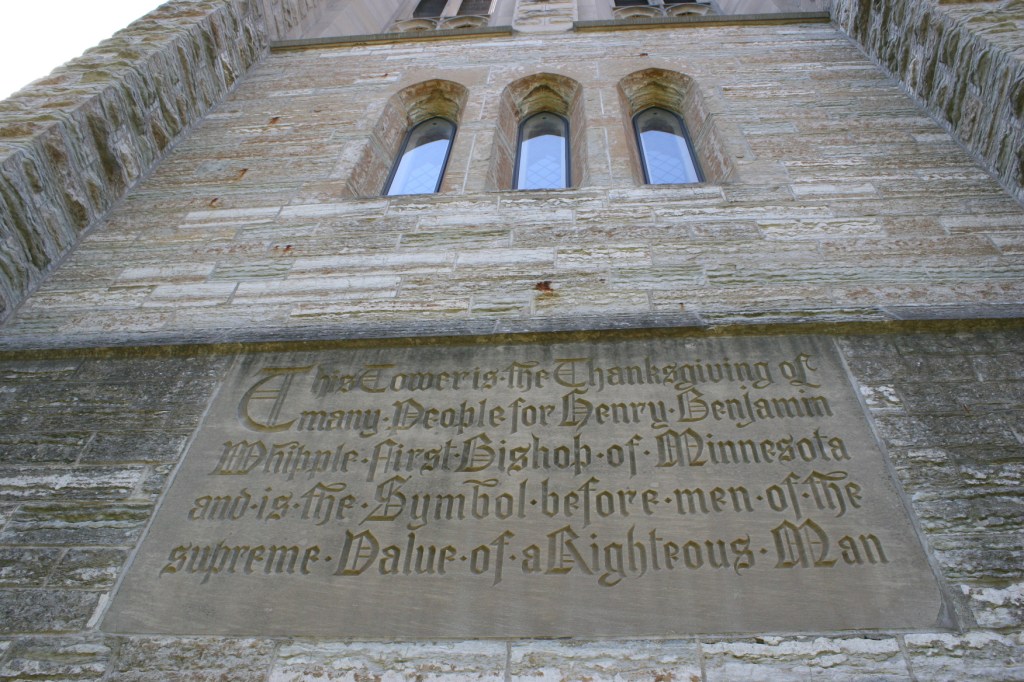

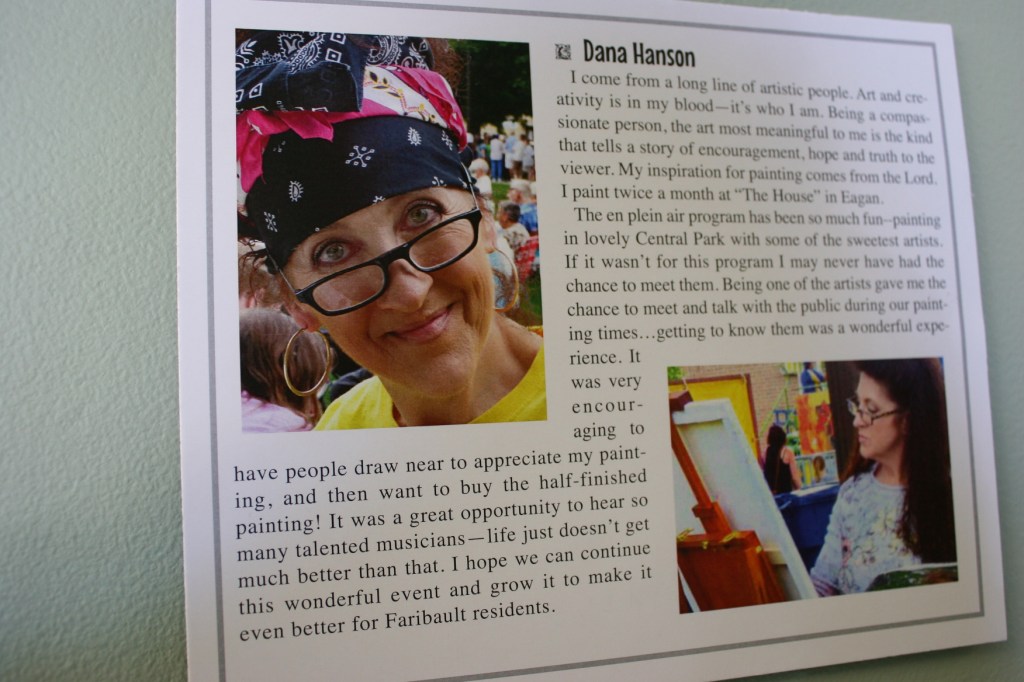

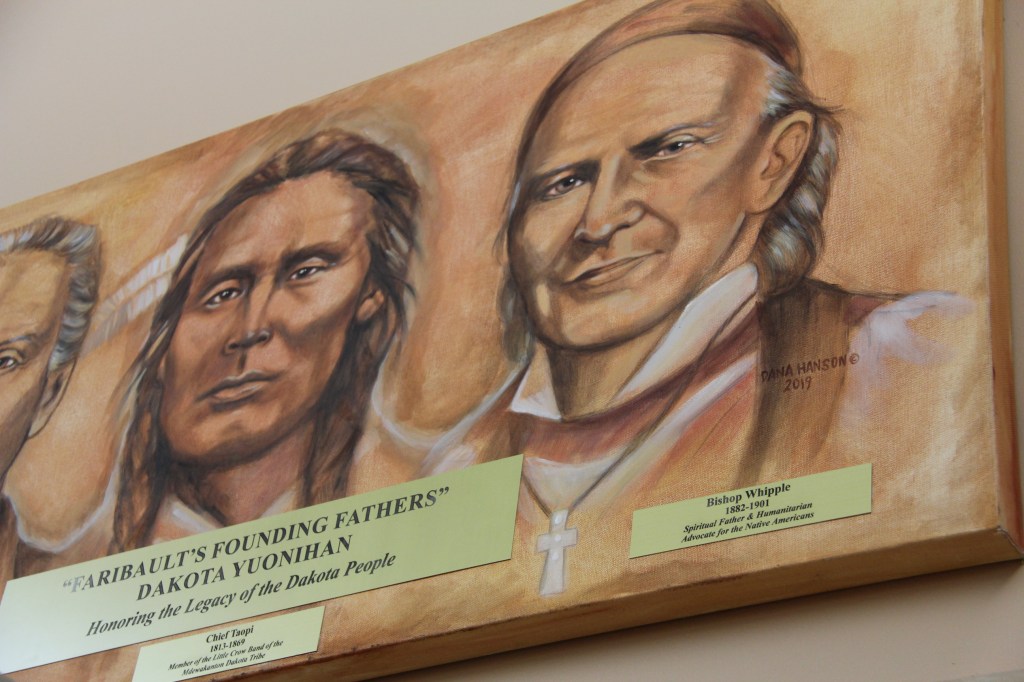

Walk around Faribault today and you will see many reminders of the work Whipple did not only locally, but across Minnesota. Historical markers and inscriptions about the bishop grace The Cathedral of Our Merciful Saviour, his faith base. He’s buried under the altar there. Across the street at Central Park, Whipple-themed murals cover the west side of the historic bandshell. Downtown, one of many history-focused benches honors Whipple. And across town, at the Chapel of the Good Shepherd on the campus of Shattuck-St. Mary’s School, a marker notes his role in founding Shattuck and other schools in Faribault.

Efforts are underway now locally to recognize the Dakota as well, to publicly mark their place in the history of Faribault. I’d like to think Bishop Henry Whipple, also known as “Straight Tongue” and “The Sympathizer,” would welcome the idea, would even step up to fund raise, just as he did some 160 years ago to support the relocation of 180 Dakota from Fort Snelling to Faribault.

© Copyright 2023 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments