WE GATHERED. On a day when I learned that a friend, an American citizen, was recently racially-profiled and stopped by ICE. On a day when I learned that ICE vehicles have been parked in my neighborhood. On a day when several Minnesota children were released from federal detainment in Texas. On a day when the border czar announced the draw-down of 700 federal agents (out of 3,000) in Minnesota. On this early February day, 75 of us gathered for an “Evening Prayer Service for Our Nation” at the Cathedral of Our Merciful Saviour in Faribault, Bishop Henry Whipple’s church.

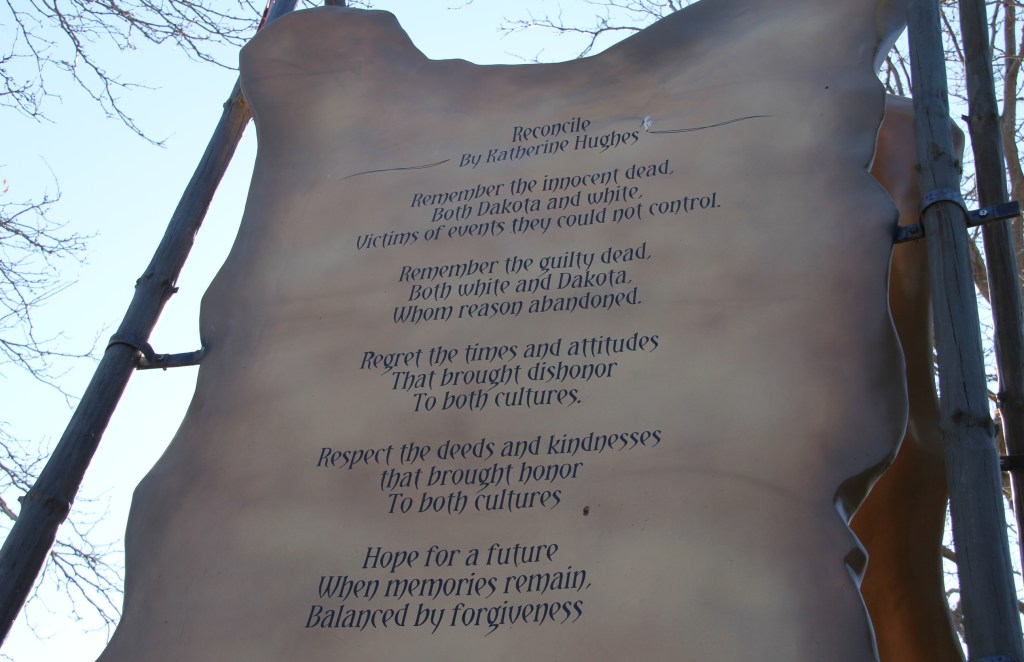

I needed this service of prayer, scripture, Psalms, reflection and hymns to quiet my troubled spirit. But I needed, too, to hold space, to sit and stand and sing and pray in community, in support of anyone—especially our immigrant and refugee neighbors—illegally stopped, taken and/or detained by ICE.

This was not a protest service. Rather, this was a reflective, prayerful, unifying, worshipful coming together of people in my community who care deeply about their neighbors and about this nation.

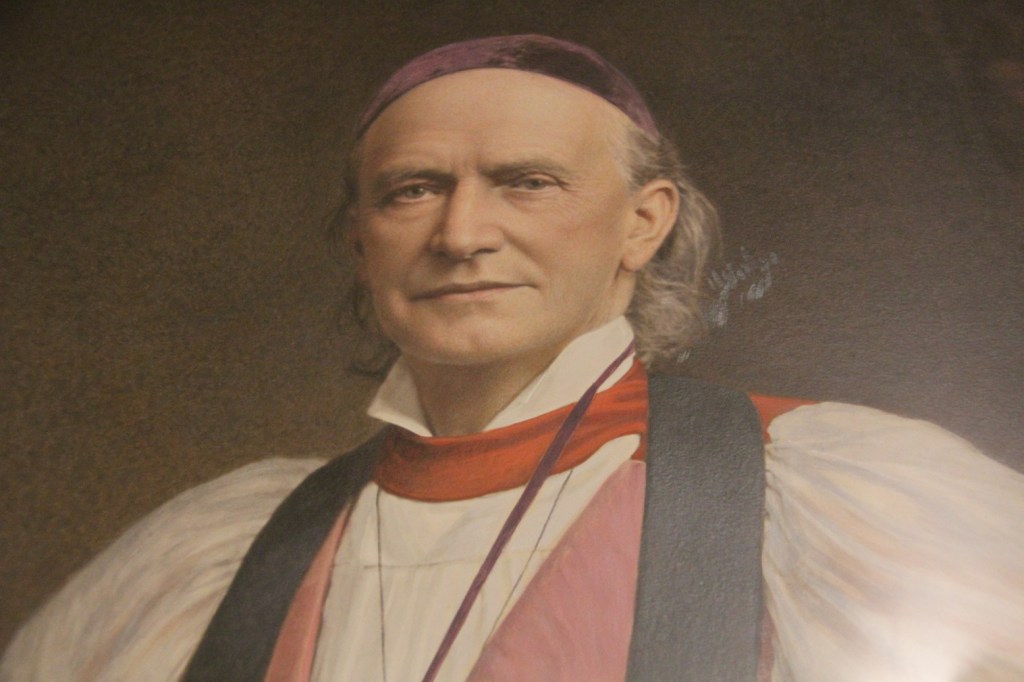

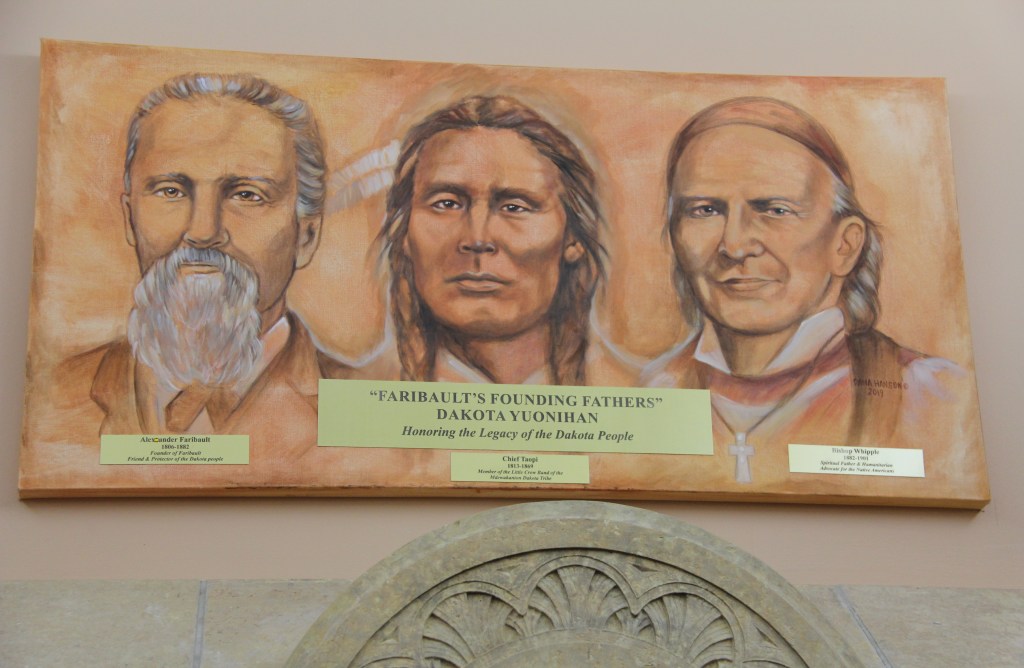

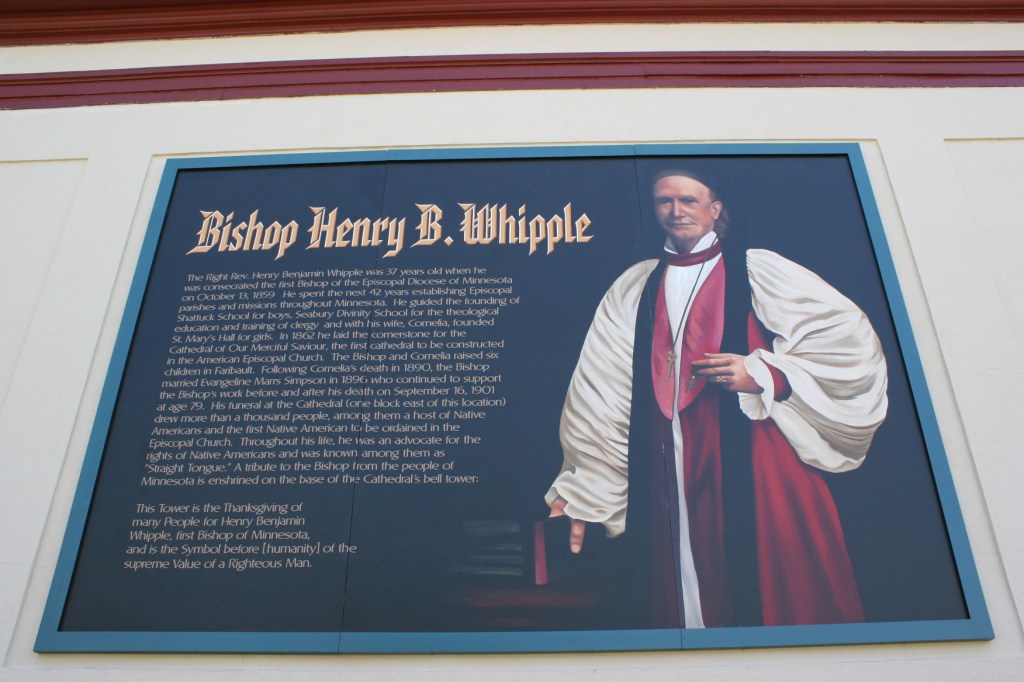

The Rev. James Zotalis welcomed attendees to the event held inside the massive Episcopal cathedral completed in 1869 under the leadership of Bishop Whipple. “Welcome to the Whipple building,” Zotalis said in opening his short homily. “This is the real Whipple building.”

He contrasted the beautiful church to the stark seven-story Whipple Federal Building 50 miles to the north that bears the good bishop’s name and which is now a temporary detention center for those detained by ICE in Minnesota. Conditions inside have been described as “inhumane” by officials who have visited the facility.

The cathedral, Zotalis said, is a place of love and peace, its ministry modeled after that of Bishop Whipple and his first wife, Cornelia. Arriving here from Chicago in 1859, the couple had already served in dangerous areas of that city, connecting with people in tangible, helpful ways, much like we see Minnesotans stepping up and helping others today.

With a repeated directive to “always say no to evil,” Zotalis said Minnesotans have done just that since the invasion of our state by masked federal agents two months ago. He listed specifics: bringing food to people afraid to leave their homes, providing rides, offering free legal aid and peacefully protesting.

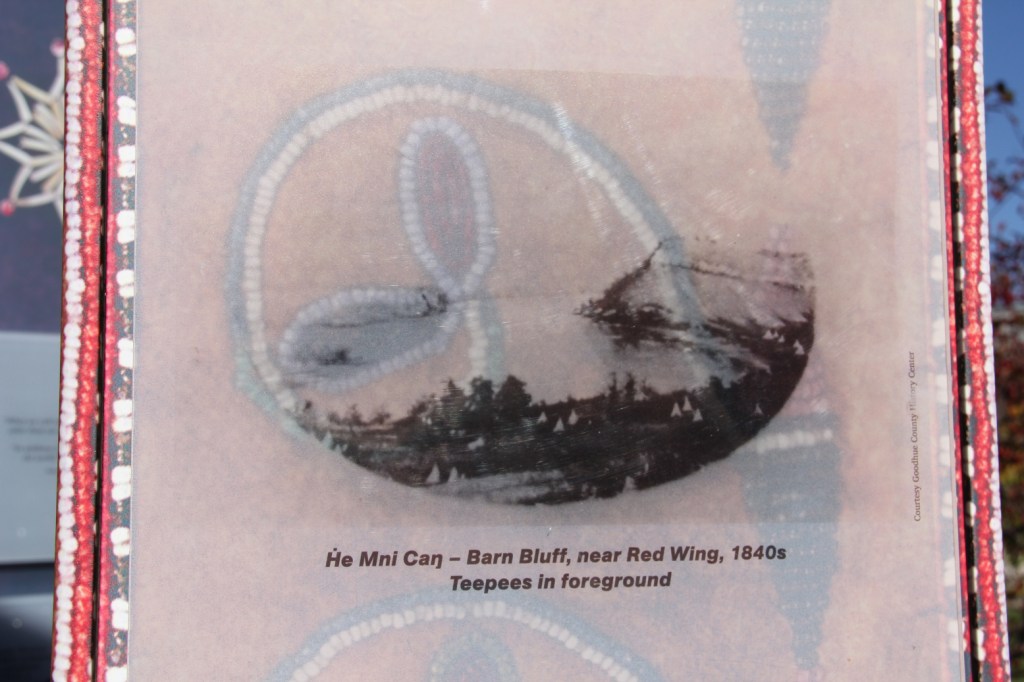

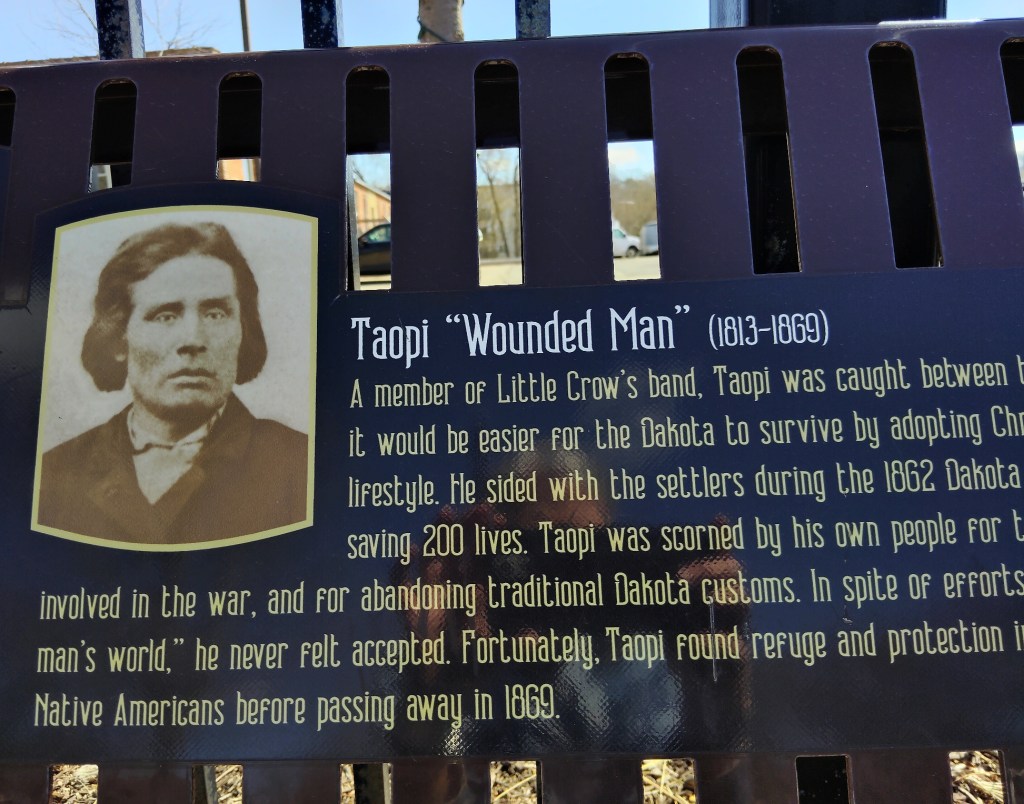

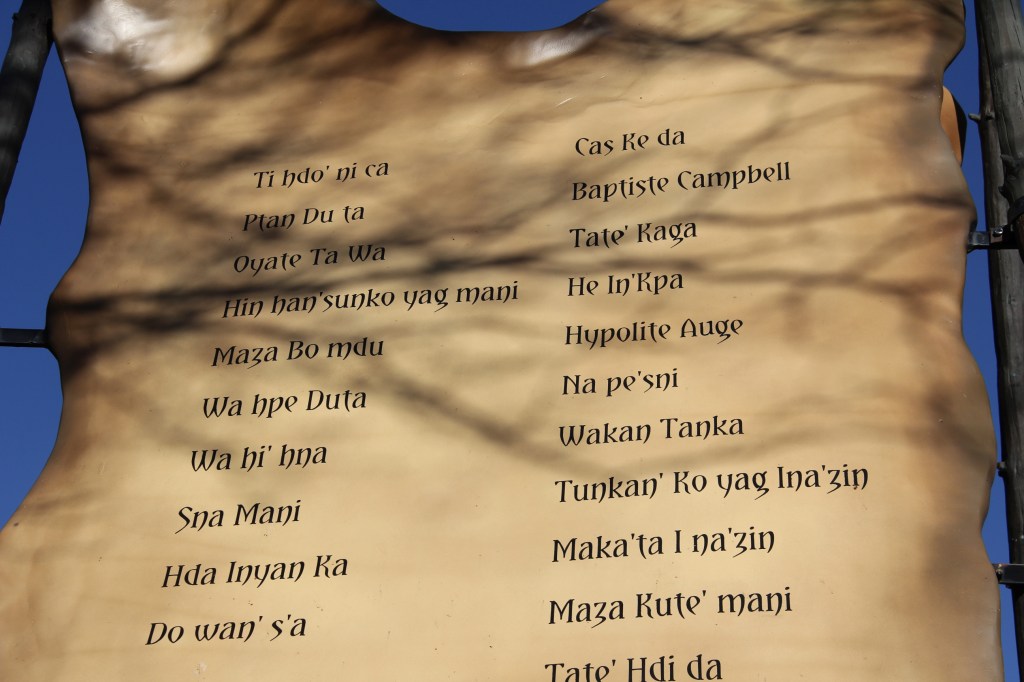

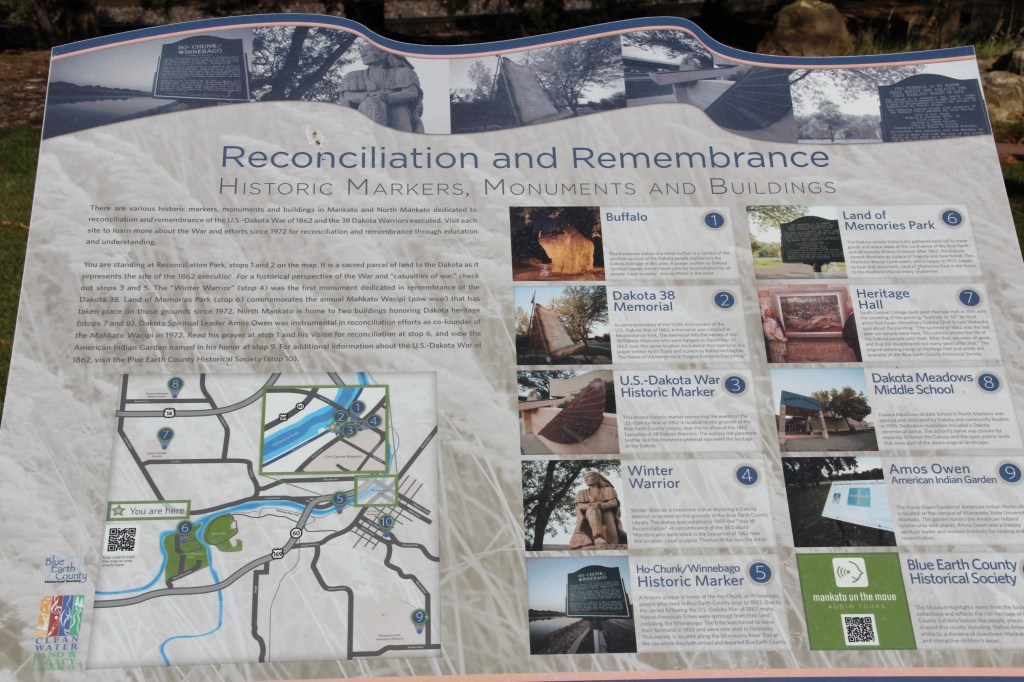

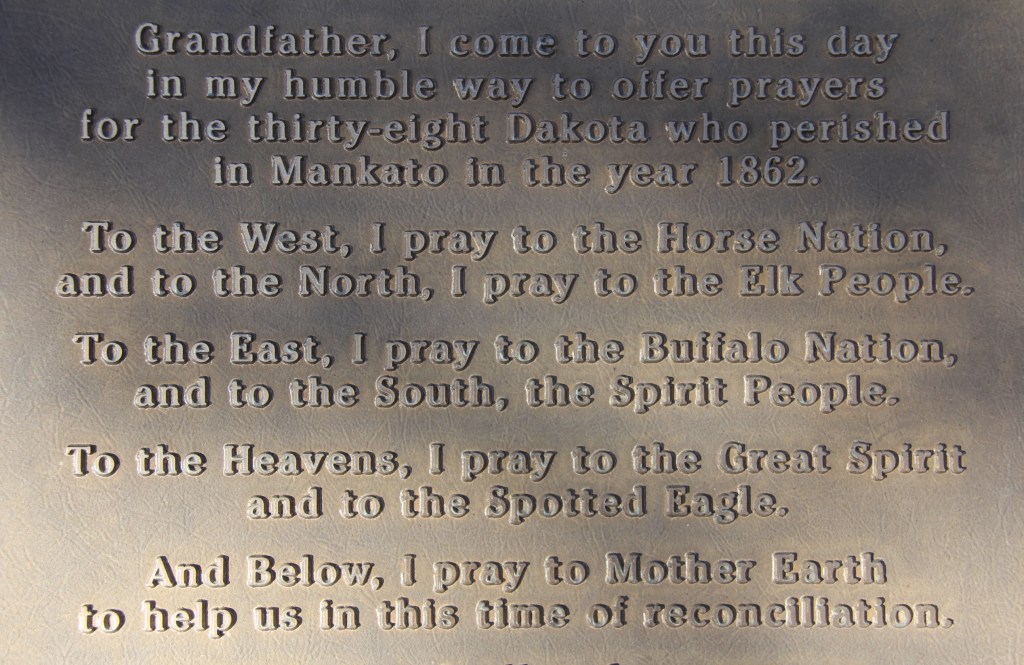

“Love your neighbor as yourself” was emphasized often in love-themed Scripture readings (Luke 10:27, I Corinthians 13:13, I John 4:11) during the Wednesday evening service. Like the good people of Minnesota today, Bishop Whipple showed that love long ago in his ministry to the Dakota people locally, across the state and during their imprisonment after the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 at Fort Snelling, where the Whipple Federal Building is located. Whipple faced death threats for those who opposed his compassionate work with Native Americans.

Death. In a time of remembrance during Wednesday’s service, attendees could speak the names of “deceased and alive during this time of tragedy and strife.” I spoke first: “Renee Good.” Then another voice: “Alex Pretti.” And then an attendee read the names of 32 individuals who died in ICE detention in 2025. Thirty-two.

Many times my emotions verged on tears. As we asked, “Lord, keep this nation under your care.” As we sang “America the Beautiful.” As we prayed a Collect for Peace. As I thought of Jesus, who also lived in troubled times and who served with love and compassion.

Theme words of love, compassion, mercy and neighbor threaded throughout the service led by the reverends Zotalis and Henry Doyle. I could feel those words. And I could feel, too, the collective sense that we all needed this evening of prayer, scripture, Psalms, reflection and hymns to quiet our troubled spirits.

FYI: To watch a video of the service online, click here.

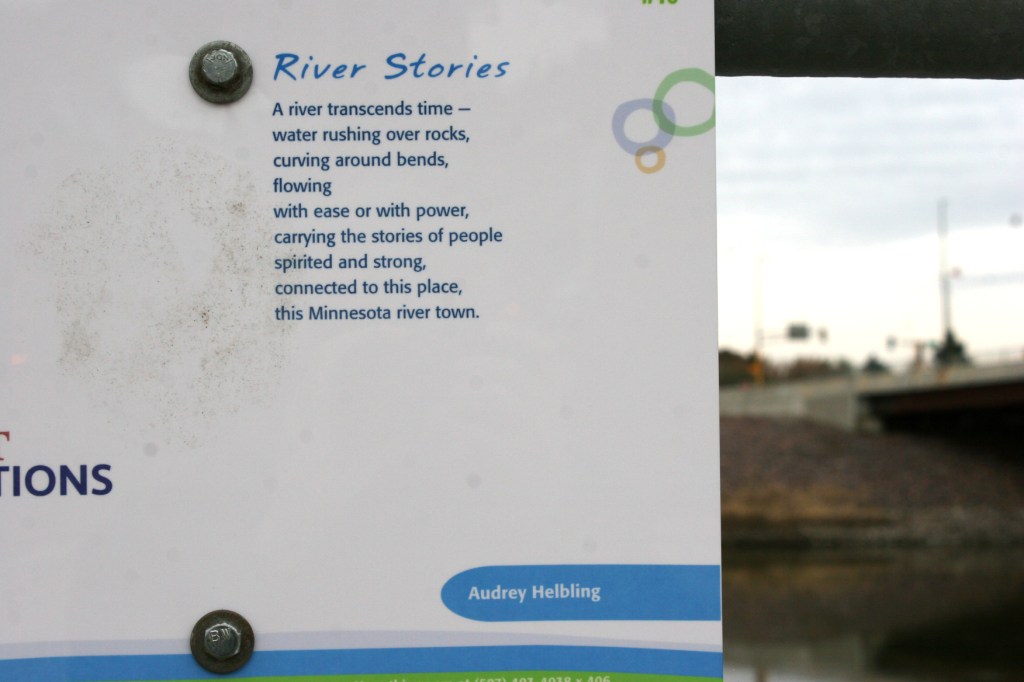

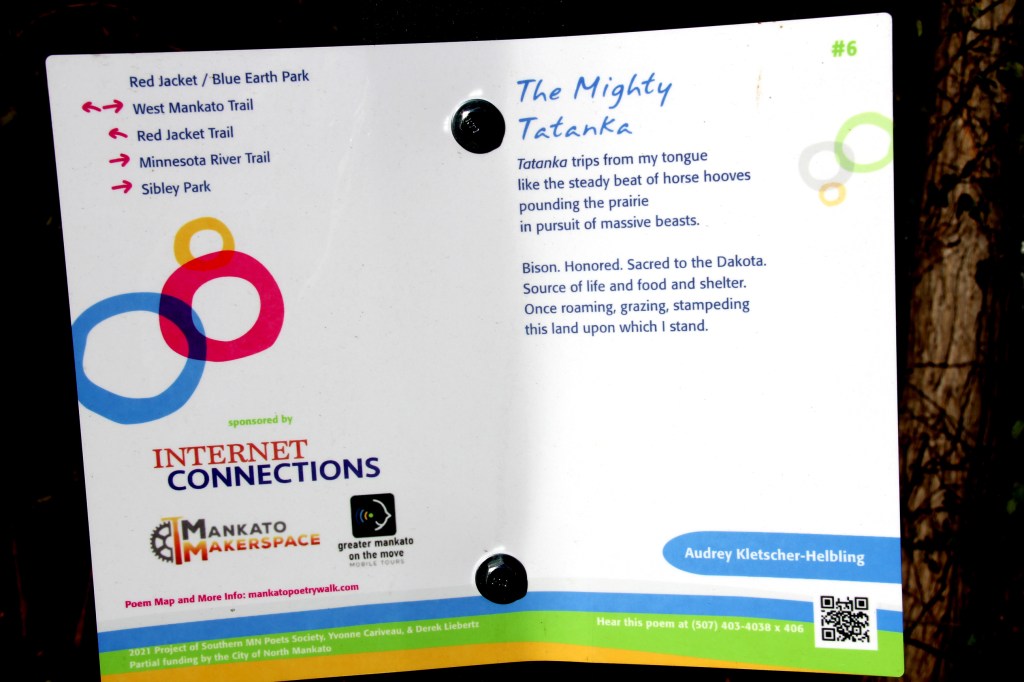

© Copyright 2026 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Bishop Henry Whipple, the man behind the federal building bearing his name January 16, 2026

Tags: advocate, Bishop Henry Whipple, Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, commentary, Dakota, faith, Faribault, history, immigrants, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, immigration enforcement, injustice, Minnesota, news, opinion, The Cathedral of Our Merciful Saviour

I EXPECT BISHOP HENRY WHIPPLE may be turning over in his grave under the altar inside the Cathedral of Our Merciful Saviour in Faribault. He would be appalled by what’s happening in this community with ICE enforcement. And he would also likely be standing side-by-side with protesters outside the Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building at Fort Snelling protesting ICE’s presence in Minnesota. The federal agents are based inside the building named after him.

Whipple was all about compassion and embracing others, especially as a friend to the Dakota in Minnesota following his arrival here in 1860 and throughout his ministry. He would not be fine with ICE violently, or non-violently, taking people from their vehicles, their homes, clinics, outside schools and churches, inside businesses…and illegally detaining them without due process. That includes those here legally and American citizens imprisoned inside the building bearing Whipple’s honorable name.

I am not OK with this. None of us should be.

HOW BISHOP WHIPPLE MIGHT REACT

As Minnesota continues to deal with the presence of 3,000 ICE agents in our state, I think of the Episcopalian bishop, known as “Straight Tongue” for his honesty, and how he would react. He would assuredly be on the streets advocating for human rights. He would be talking with the current president, just like he did in 1862 with President Abraham Lincoln. Whipple traveled to DC then to personally plead for the lives of 303 Dakota sentenced to death by hanging.

Whipple would probably also be out buying groceries for Faribault residents afraid to leave their homes. He would be walking kids to their bus stops in trailer parks. He would be preaching peace, love and compassion.

HONORING WHIPPLE’S LEGACY

Those who disliked Whipple, and the Dakota, disparagingly tagged the clergyman as “The Sympathizer.” Little has changed. There are far too many in my community who hate, and, yes, that’s a strong word, anyone whose skin color is other than white. I don’t understand. They all, unless they are Native American, can trace their presence in America back to immigrants.

If only Bishop Henry Whipple was still alive to spread love in Faribault and beyond. It’s up to us to honor his legacy by loving and helping our neighbors during these especially dark days of injustice and oppression.

#

FYI: To learn more about the bishop, I direct you (click here) to a previous blog post I wrote about him and his role in Minnesota history following a 2023 presentation at the Rice County Historical Society.

© Copyright 2026 Audrey Kletscher Helbling