UNDER A SUNNY February sky, they gathered in communion around fire pits outside two historic Norwegian immigrant churches high atop a hill in eastern Rice County. Food, fellowship and a fondness for this place drew people here, to the fourth annual Doughnut Hole Roasting Party.

For the first time, I attended this event, although I’ve been to the Valley Grove churches and the adjacent cemetery many times. I love this secluded spot near Nerstrand, where historic wood-frame and limestone churches rise above the surrounding countryside in an especially picturesque setting. There are prairie trails to hike here and an oak savanna. It’s peaceful here.

On this balmy Sunday afternoon of unseasonably warm temps in the mid-fifties, sweatshirt or light jacket weather, conversations broke the quiet. The mood felt engaging, connective, of communion in community.

Hosted by the Valley Grove Preservation Society Board, the roasting of doughnut holes was also an event to raise monies for ongoing preservation and restoration projects at the 1862 stone and 1894 wooden churches. Both churches are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Even with no personal connection to these churches or the Norwegian heritage, I understand the historical importance of these immigrant churches. Step inside either church and you can almost feel the strength of those early Norwegians who crossed the ocean, started a new life in Minnesota, built first the now 164-year-old stone church and then the 132-year-old wood-frame church.

The stone church serves today primarily as a social gathering spot. The wooden church still hosts the occasional service—a wedding, a funeral and the annual Christmas Eve worship. Other celebrations like Syttende Mai, a wedding anniversary reunion and a country social are also held annually at Valley Grove.

But on this day, we focused on doughnut holes forked onto metal roasting sticks and held over an open flame. Some roasted their treats to coal black, to caramelize the doughnuts I was told. Not fond of charred anything, I preferred mine heated then dipped in chocolate. They were sweet and tasty and messy. I found a shadowed patch of remnant snow to “wash” my sticky fingers.

Although I knew only one person here, I made a new friend, Mary, who sat with her dog on a stone memorial bench in the cemetery, sunshine beaming warmth upon them. Others meandered through the graveyard where early Norwegian immigrants, their descendants and others lie buried beneath the cold earth.

On the dormant lawn between the two churches, people clustered—standing, sitting in lawn chairs, bending, reaching over flames to roast doughnut holes on a Sunday afternoon in mid-February in southern Minnesota.

© Copyright 2026 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

“Evening Prayer for Our Nation” planned at Bishop Whipple’s church in Faribault February 2, 2026

Tags: "Evening Prayer for Our Nation", America, Bishop Henry Whipple, Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Cathedral of Our Merciful Saviour, commentary, community gathering, faith, Faribault, history, immigrants, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Minnesota, news, prayer service, refugees, social justice

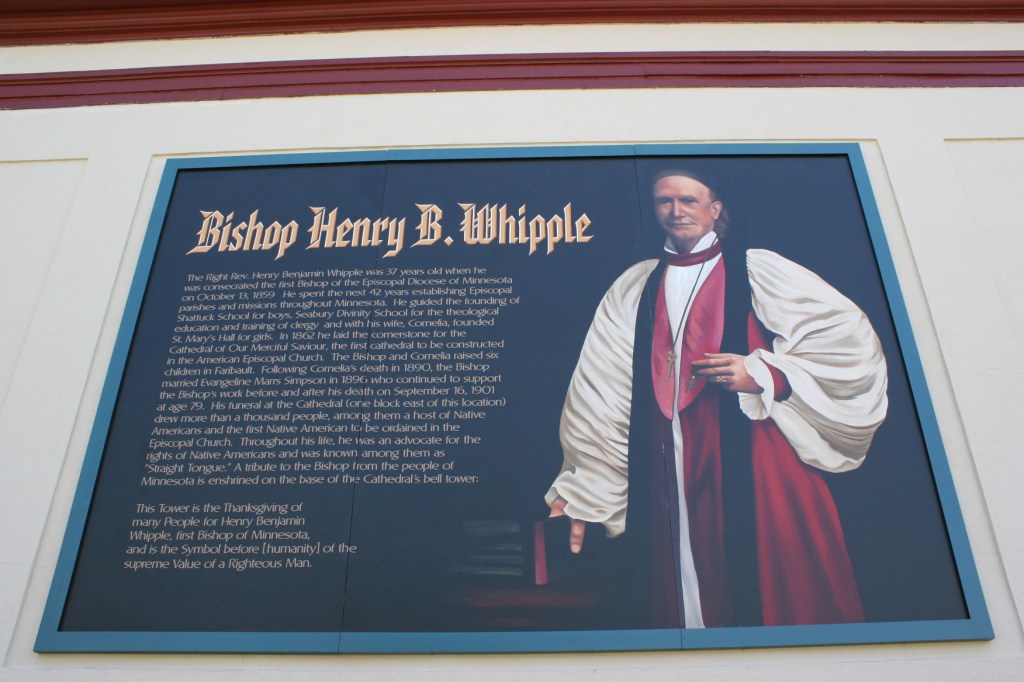

FIFTY MILES FROM THE NON-DESCRIPT Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building currently housing ICE detainees in Minneapolis, a beautiful, aged cathedral rises high in the heart of Faribault. Wednesday evening, February 4, that magnificent, massive cathedral—Bishop Whipple’s church—will center a community gathering.

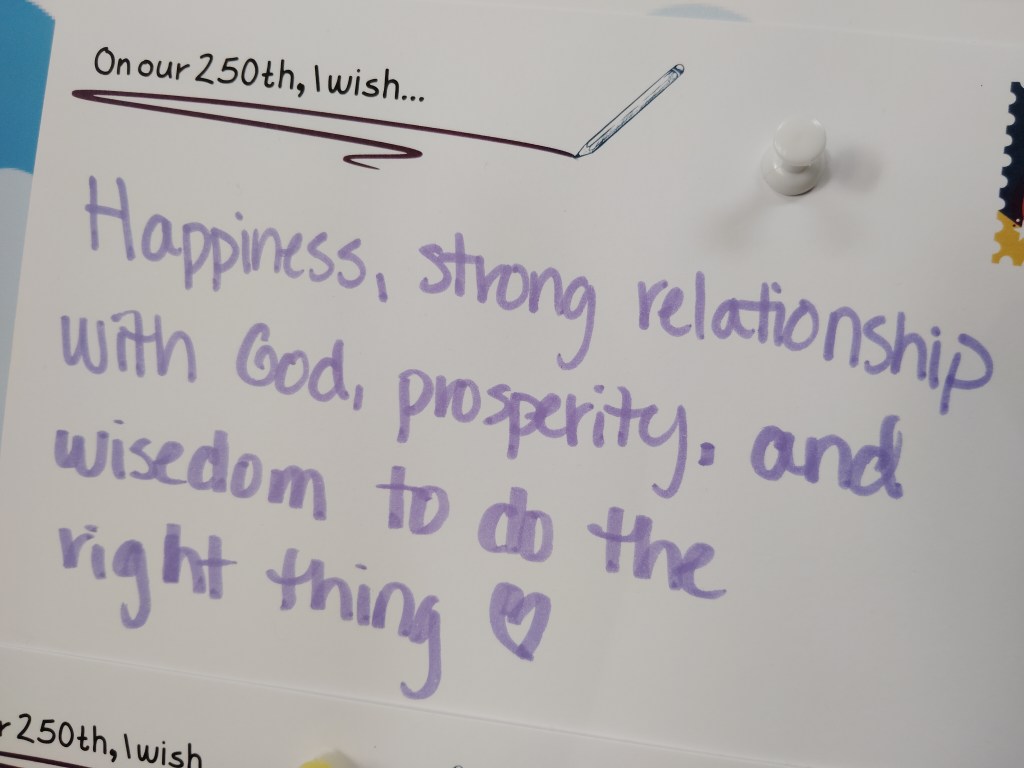

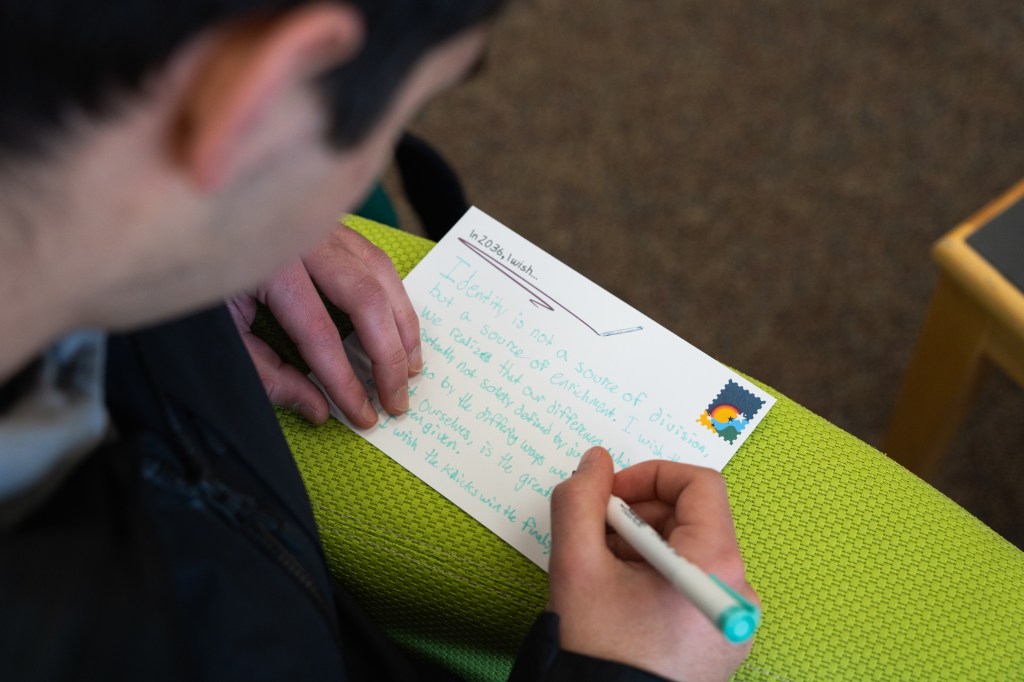

Beginning at 7 p.m. the historic Cathedral of Our Merciful Saviour will open its doors for “Evening Prayer for Our Nation” in support of Faribault’s refugees and immigrants. The Cathedral’s pastor, the Rev. James Zotalis, and the Rev. Henry Doyle will lead the event, which includes prayers, readings, music and teachings from Bishop Whipple.

Organizers also promise networking opportunities and information about ways to help others.

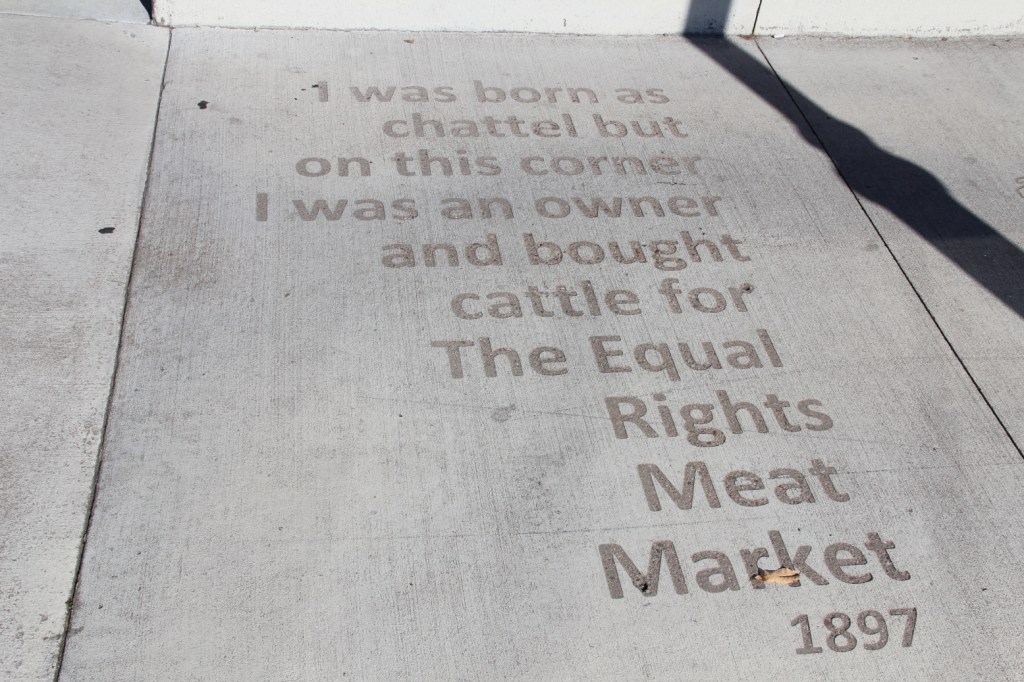

Bishop Whipple, who shepherded this congregation while serving as the first Episcopal bishop of Minnesota beginning in 1859, would surely be pleased with the upcoming gathering just as he would surely be displeased with the imprisonment of detainees at the federal building bearing his name. He would likely be standing alongside protesters protesting immigration enforcement and asking to visit detainees inside.

This clergyman focused his ministry on “justice and mercy for all.” And that is evidenced in his ministry to the Dakota both in Faribault and parts west in Minnesota and then at Fort Snelling. Whipple went to the fort and ministered to the Dakota held captive there following the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

When 303 Dakota were sentenced to hanging after the war, Whipple traveled to Washington DC to ask President Abraham Lincoln to spare their lives. Lincoln pardoned most, but 38 were still hung in the nation’s largest mass execution.

If Bishop Whipple was alive today, I expect he would be doing everything in his power to help anyone threatened and/or taken by ICE and CBC. But because he is not here, it is up to us to help. I know many people in my community are helping quietly behind the scenes. Walking kids to bus stops. Giving co-workers rides. Delivering groceries. Donating money and food. Volunteering.

Wednesday evening’s “Evening Prayer for Our Nation” is needed, too. It’s needed to bring people together in community, to unite, to uplift, to pray, to share, to recharge, to publicly support our neighbors, to find tangible ways to help. Bishop Whipple would feel grateful. He cared. And so should we.

#

FYI: Whether you live near or far, Faribault nonprofits are in need of donations to help families sheltering in place during ICE operations in Minnesota. This is not just a Twin Cities metro enforcement. Many communities in greater Minnesota, including mine, are suffering.

Please consider helping immigrants and refugees in my community via a monetary donation to the Community Action Center in Faribault (Community Response Fund) or to St. Vincent de Paul. The need for rental assistance, especially, is growing.

© Copyright 2026 Audrey Kletscher Helbling