AT THE BASE of He Mni Caɳ, also known as “Barn Bluff,” I contemplated whether to climb the 340-foot cliff rising high above the Mississippi River in southern Minnesota. It seemed like a good idea when Randy and I were considering just that on our drive from Faribault to Red Wing recently. But reality set in once we found the bluff, started up a steep pathway and determined that this might be a little much for two people pushing seventy. My vision issues and fear of heights also factored into discontinuing our hike.

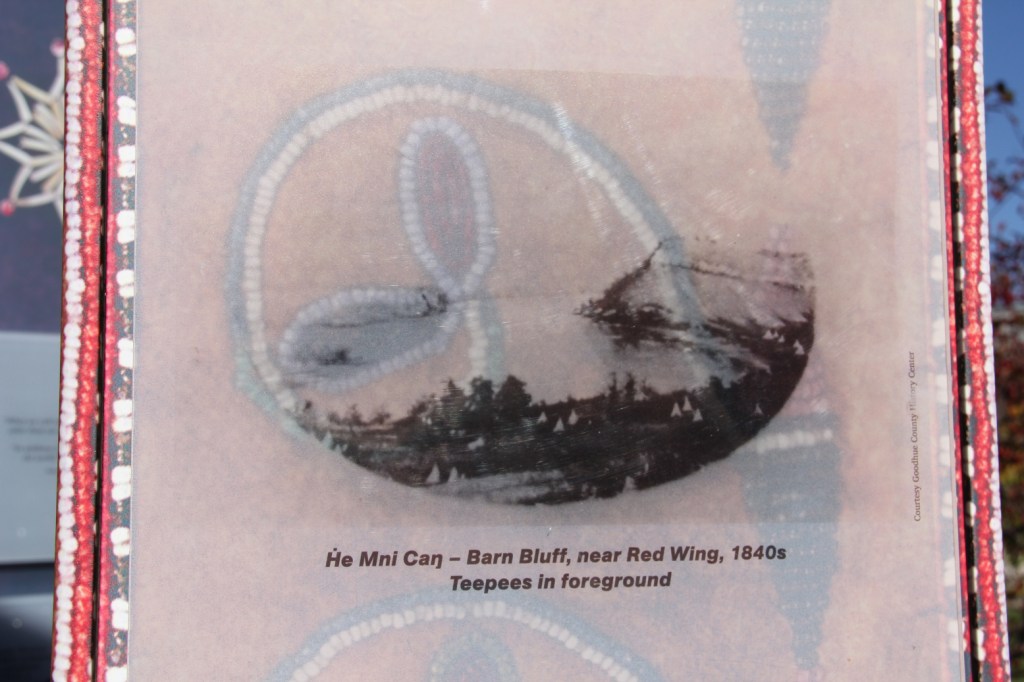

While disappointed, I was still thankful we were here because He Mni Caɳ holds historical, cultural and sacred significance for the Bdewakantunwan Dakota Oyate, the Indigenous Peoples who originally inhabited this land. They lived on land below and around the bluff on the site of current-day Red Wing. They held ceremonies and rituals atop the bluff, also used for burial, shelter from enemies and more. This was, and always has been, a sacred place to the Dakota.

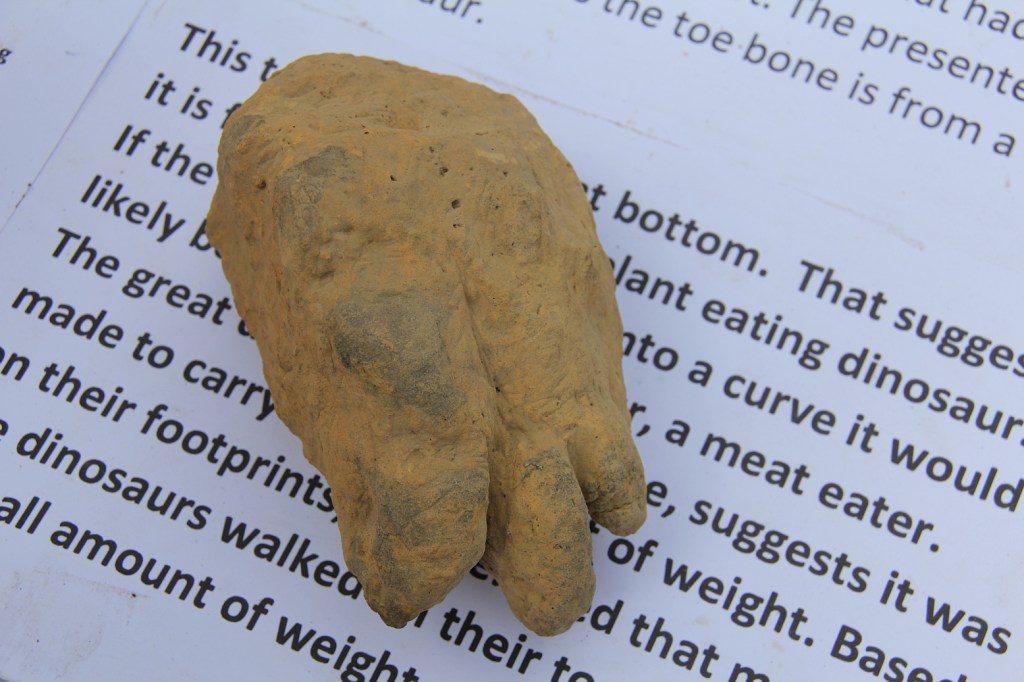

That message is shared in an Entrance Plaza to He Mni Caɳ. There storytelling markers and seven towering pillars reveal details about this place and its importance to Native Americans. Via images, words and art, I began to learn, to understand. By learning, I am also honoring National Native American Heritage Month celebrated in November.

I admittedly did not read every single word and somehow missed noticing the buttons to push on the storytelling markers that would allow me to hear the spoken Dakota language. But I still gathered enough information, enough story, to recognize the value of this land to the Dakota and the respect we should all hold for them, their history and the sacred He Mni Caɳ, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The city of Red Wing and the nearby Prairie Island Indian Community have partnered to preserve and honor this place along the Mississippi following the guiding principles of heal, sustain, educate and honor. I saw that and read that in the plaza.

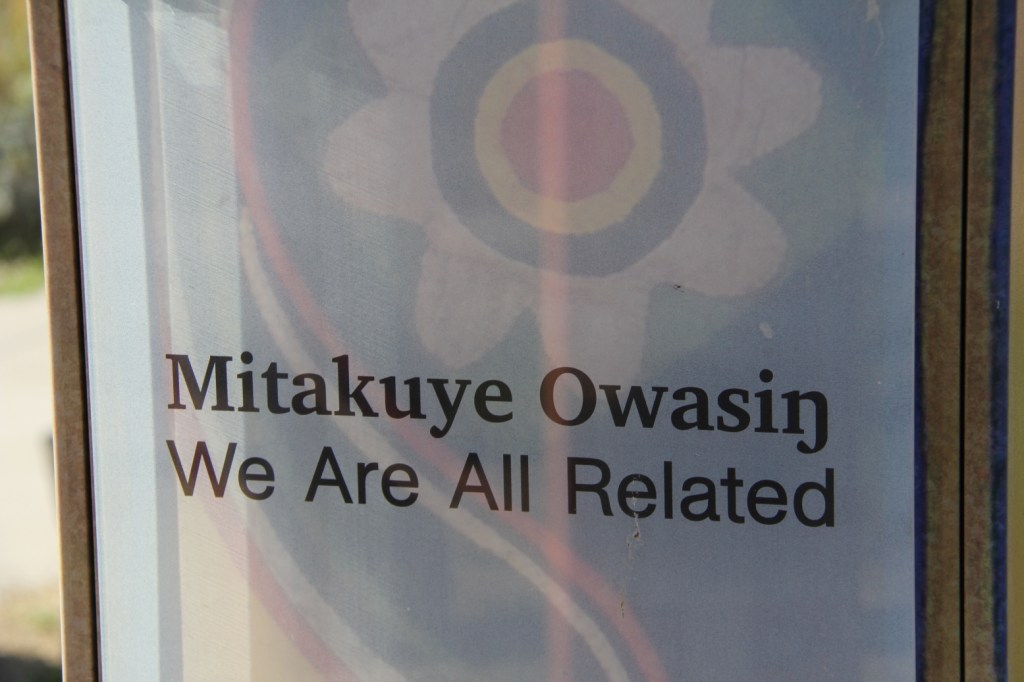

As I viewed the historic Dakota patterns on the seven plaza columns and walked around this history circle reading and photographing, words and phrases popped out at me: We are all related. Interconnectedness. Kinship and a shared landscape. If only, I thought, we would all hold those words close, remember them in our differences, remember them in our relationships with each other and with the earth, remember them in our struggles and disconnect.

The city of Red Wing is named after Tatanka Mani (“Walking Buffalo”), long ago leader of the Mdewakanton Dakota in the upper Mississippi River Valley. Early immigrants who settled in the area gave him that name. Tatanka Mani helped shape the history of this region through his decisions and leadership. He was clearly connected to his people, to the non-Natives who arrived here, and to the land.

Today He Mni Caɳ/Barn Bluff remains a major attraction in Red Wing, just as it was years ago for those traveling the river, exploring the region. Henry David Thoreau, Henry Schoolcraft and Zebulon Pike are among the countless who viewed the river and river valley below from atop the bluff.

But not me. I was content to stand at its base, to take in the history shared there. And then later to view the bluff from Sorin’s Bluff in Memorial Park, a park with a road leading to the top. Even then I settled for a partial ascent, because I’d had enough of heights on this day when He Mni Caɳ challenged me and I learned the history of this sacred place.

© Copyright 2025 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

The stories of two Marthas September 19, 2025

Tags: Ariel Lawhon, books, Buckham Memorial Library, Cambodia, Camodian Genocide, commentary, Faribault, healing, historical fiction, history, Martha Ballard, Martha Brown, Minnesota, The Frozen River

HISTORY CONNECTS THE STORIES of the two Marthas. One, Martha Ballard, a midwife and the main character in a book of historical fiction, The Frozen River by Ariel Lawhon. The second Martha is Martha Brown, local author, educator, speaker, musician and political candidate for state representative in my district. She shared her personal reflections about a trip to Cambodia on Thursday evening at the Faribault library in a presentation titled “Cambodia—Healing a Broken County.”

I’d just finished reading Lawhon’s book earlier Thursday so the commonalities between a story set in the late 1700s in postrevolutionary America and Brown’s recent trip to Cambodia connected in my mind. In both stories exist violence, trauma, strength, power and resilience within an historical context.

THE CAMBODIAN GENOCIDE

I’ll start with Brown. She focused on the time before and after the 1975-1979 Cambodian Genocide in which some 2 million Cambodians were murdered under the rule of Khmer Rouge, the Communist political party then in power. She also touched on the illegal and secret bombings of Cambodia by the U.S. in 1969 against North Vietnamese forces in Cambodia. That, too, claimed untold civilian lives.

I don’t want to get into historical details here or a political discussion about the Vietnam War. Rather, I intend the focus to be on those who suffered in Cambodia and those who survived. Just as Brown focused her hour-long talk. She arrived in Cambodia expecting to see trauma from the genocide. But instead, she said, she found recovery, healing and joy. She saw survivors of the genocide as part of the healing.

A HORRIFIC HISTORY NOT HIDDEN

The history of the genocide has not been hidden nor erased in Cambodia. “They don’t bury their history,” Brown said. I jotted that quote in my notebook, mentally connecting that to current day America and ongoing efforts by the current administration to erase/hide/rewrite history. We all know the quote—”Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”—by Spanish Philosopher George Santayana. We would do well to contemplate and hold those words close.

In her presentation, Brown did not avoid the hard topics of children recruited and indoctrinated to participate in the Cambodian Genocide killings of educators, doctors, ordinary people, even those who wore eyeglasses. Perpetrators were never punished, went back to their lives, now live among the population. This was hard stuff to hear, especially about the brainwashing of children to kill. “We need to teach our children well,” said Brown, ever the educator who cares deeply about children.

LESSONS LEARNED IN CAMBODIA

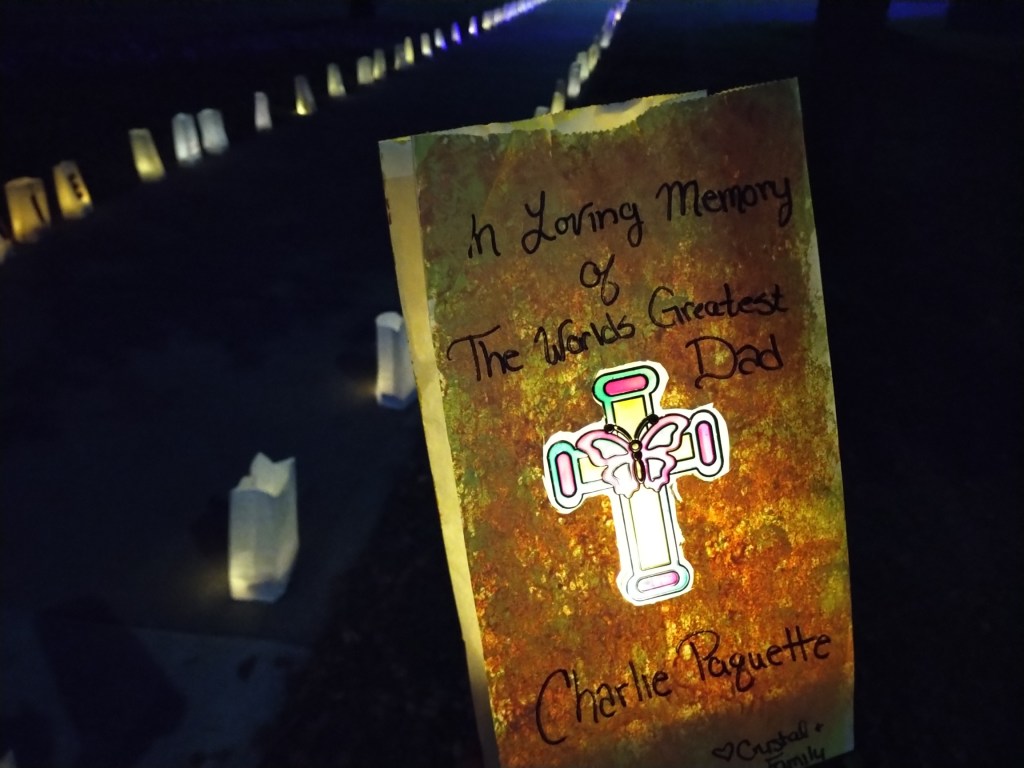

Her passion was evident as she spoke of hugging survivors, of apologizing for the U.S. bombings of Cambodia, of crying while in the southeast Asian country. She learned that how you live and treat people is more important than wealth. She learned that people can be poor and still be happy. She learned about the differences in a society that focuses on community rather than self.

When Brown’s talk ended, others shared and a few of us asked questions, including me. Mine was too political to answer in a non-political presentation. But I asked anyway about the internal and external factors contributing to the rise and fall of empires. Brown hesitated, saying only that we could draw our own conclusions from her talk.

A MUST-READ BOOK

Then I wrote “The Frozen River by Ariel Lawhon” on a slip of paper. Not to give to Brown, but rather to the local director of Hope Center serving survivors and victims of sexual assault and domestic violence and their families. I handed the paper to Erica Staab-Absher after hugging her. “You need to read this book,” I said.

In this book of historical fiction, the author bases her writing on real-life midwife Martha Ballard, who documented her life in a journal. Ballard was witness to violence, sexual assault, injustices, secrets, manipulation, power, trauma and much more. This book will resonate with anyone who has survived a sexual assault or cared about someone who has been so viciously attacked. I cannot say enough about the value of reading this book and how empowering it was to me as a woman. It is a love story, mystery and a documentation of strength and resilience.

Resilience. Strength. Healing. Those three words come to mind as I connect the work of a New York Times bestselling author and a talk about the Cambodian Genocide at my southern Minnesota library. By reading and listening, I learned. To read a book pulled from the shelves at my public library and then to listen to personal reflections about a trip to Cambodia on the second floor of that same library are freedoms I no longer take for granted. Not today. I choose to remember and learn from the past. And hope we do not repeat it.

© Copyright 2025 Audrey Kletscher Helbling