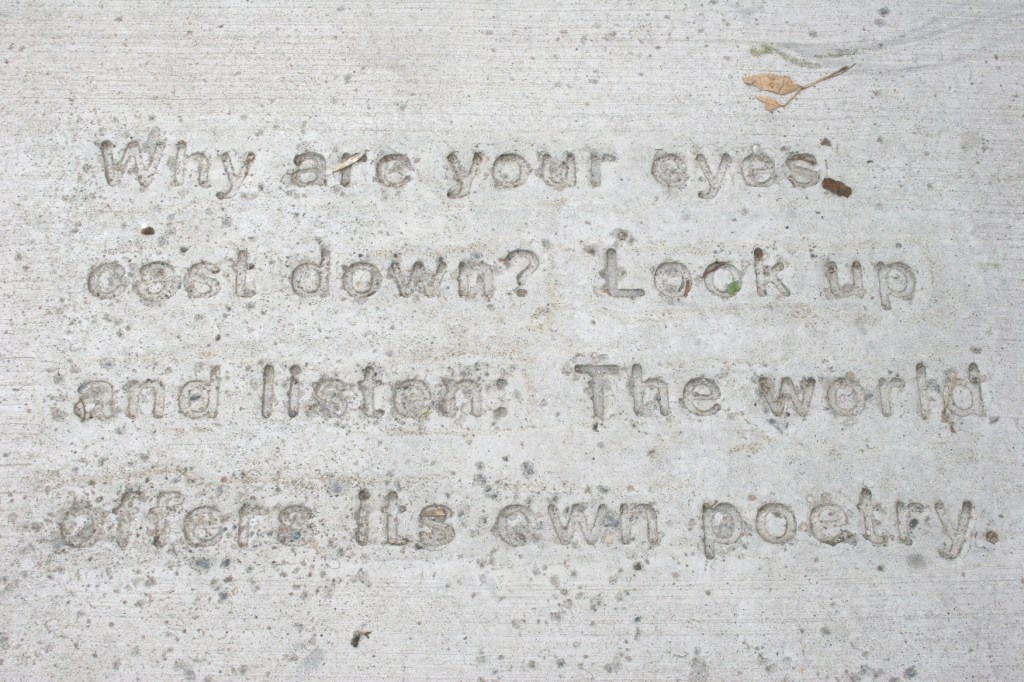

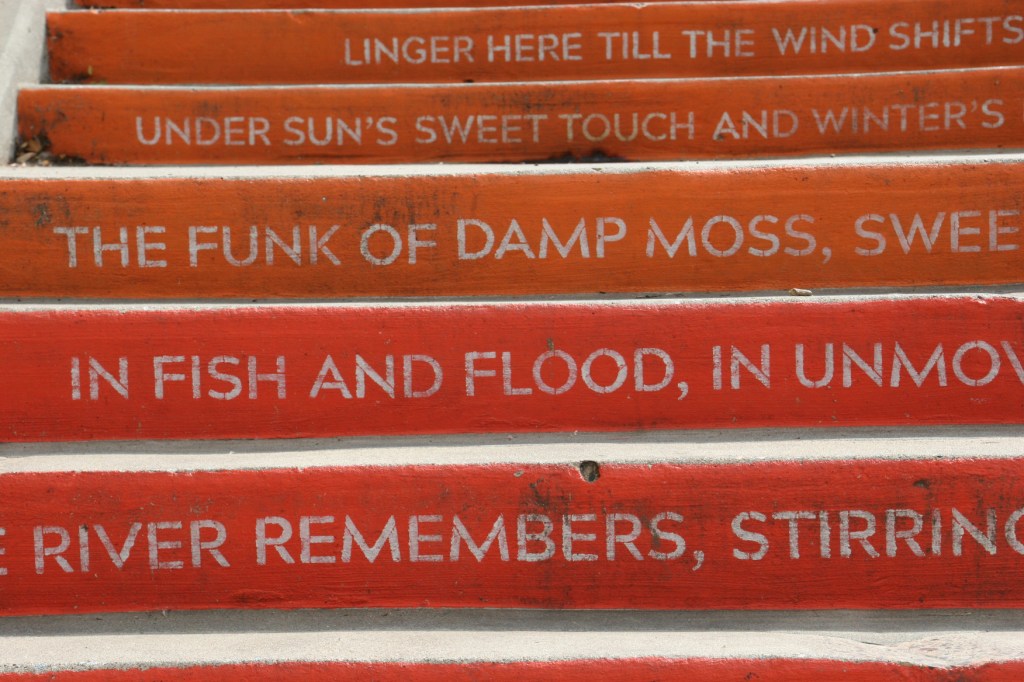

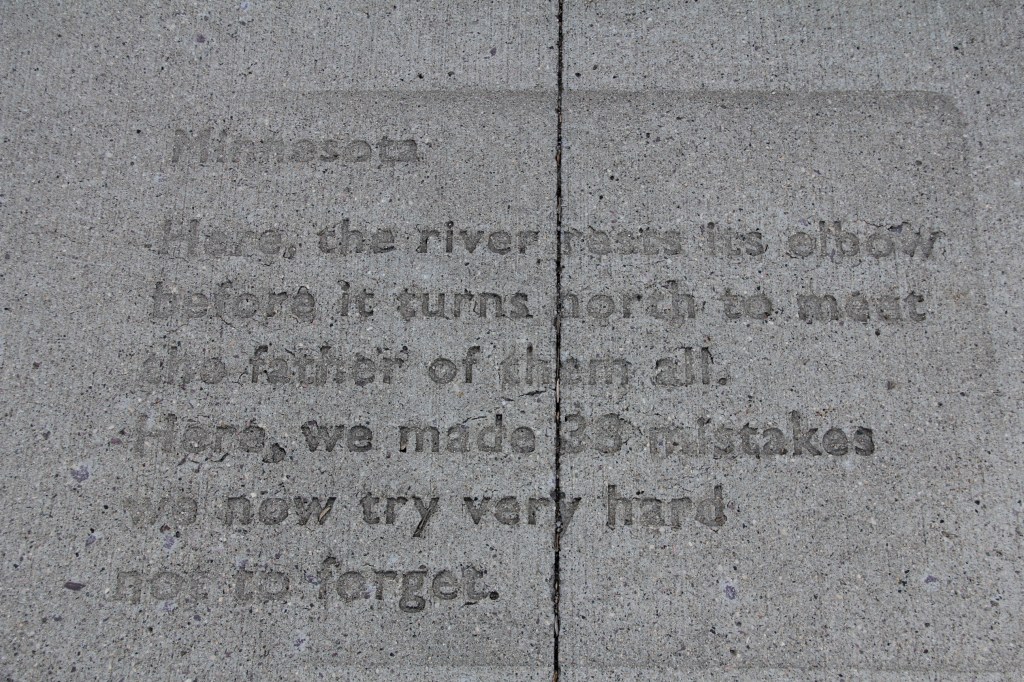

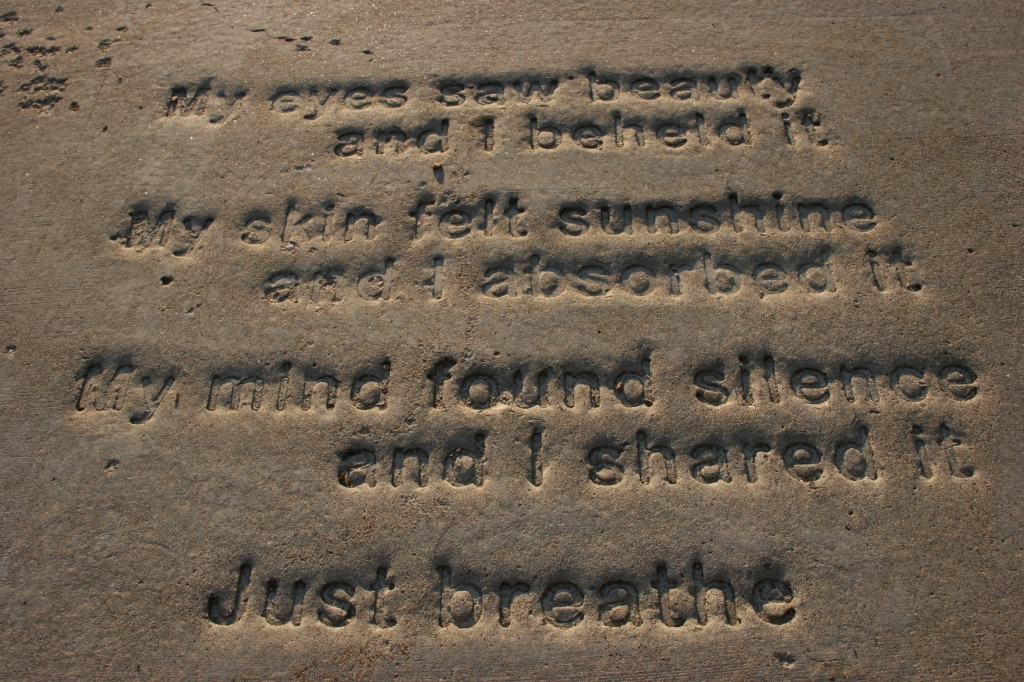

I FEEL FORTUNATE to live in an area of Minnesota which values poetry. Some 20 minutes away in Northfield, poems imprint upon concrete throughout the city as part of the long-time Sidewalk Poetry Project. Along the Riverwalk, a poem descends steps. In the public library, a poem graces the atrium.

But that’s not all in Northfield. This city of some 21,000 has a poet laureate, currently Russ Boyington, who fosters poetry, organizes and publicizes poetry events, and leads an especially active community of wordsmiths. These are published poets, serious about the craft.

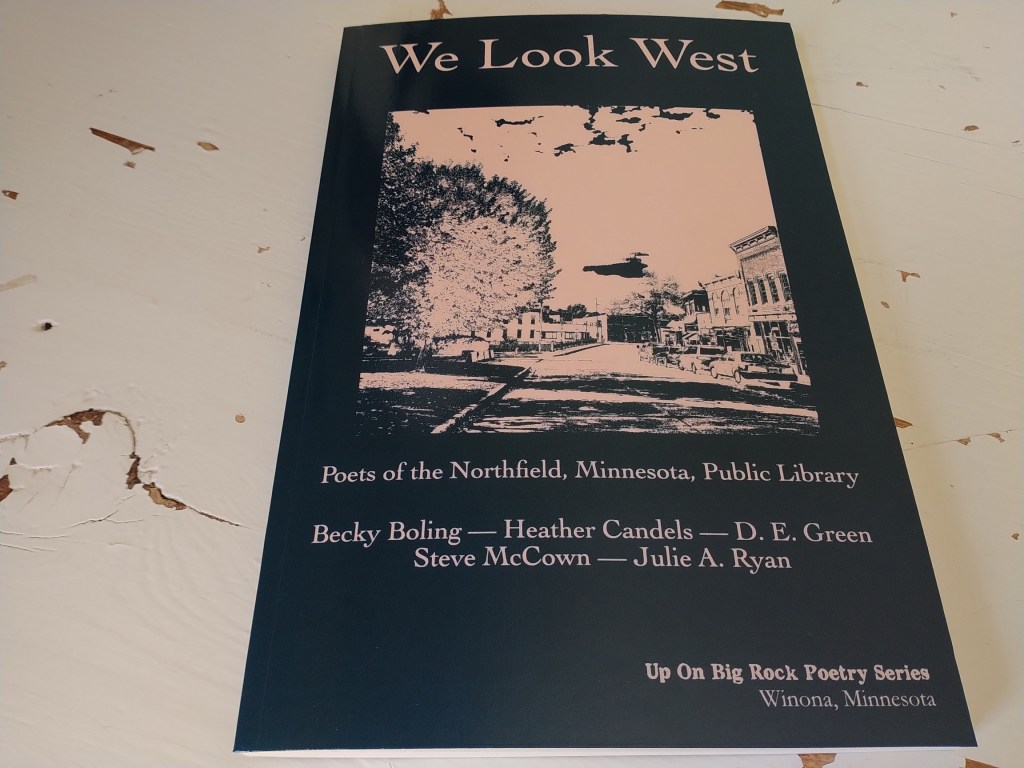

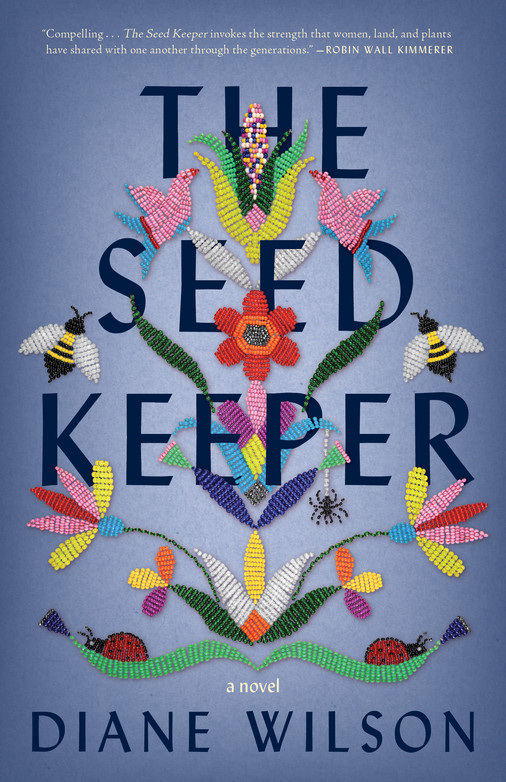

Five seasoned Northfield poets recently collaborated to publish a collection of their work in We Look West. Even if you think you don’t like poetry, you will find something in this anthology which resonates. These poets take the reader through the seasons of life with humorous, sad, nostalgic, reflective and introspective poems. This anthology is especially fitting for anyone closer to the sunset, than the sunrise, of life.

April, National Poetry Month, marks a time to celebrate poets like those in Northfield and beyond. In my own community of Faribault, we have an especially gifted poet, Larry Gavin, a retired high school English teacher and writer. He’s published five collections of his work. Larry writes with a strong sense of place, his poems reflective of his love of nature, of the outdoors. A deep love of the prairie—he attended college, then lived and worked for a while in my native southwestern Minnesota—connects me to this remarkable poet. Plus, Larry has the rich voice of a poet, which makes listening to him read his poems aloud an immersive, joyful experience.

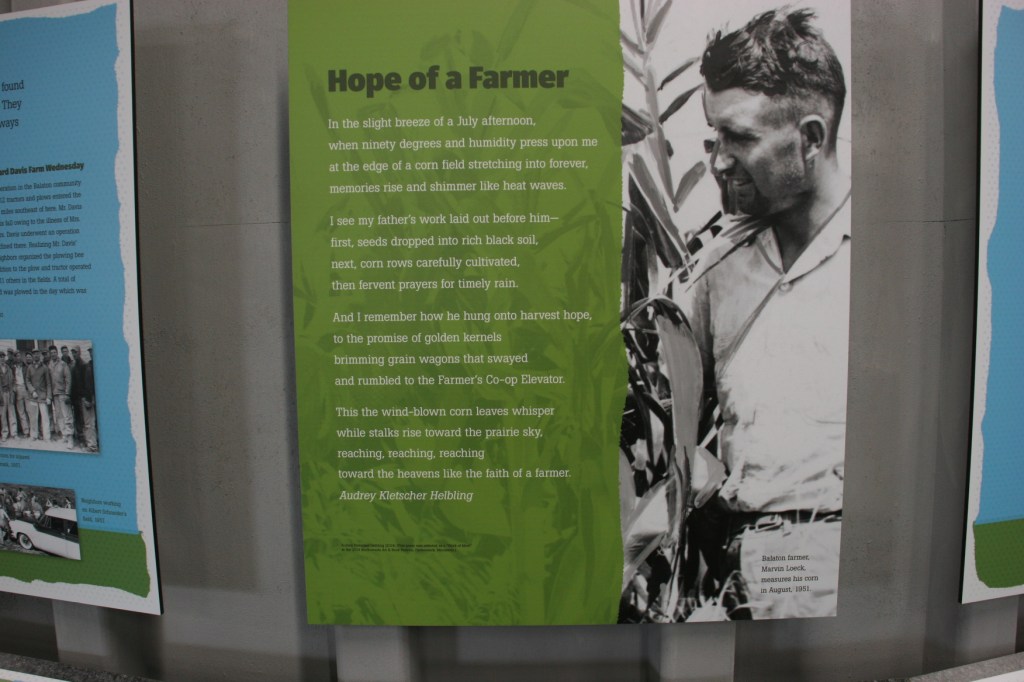

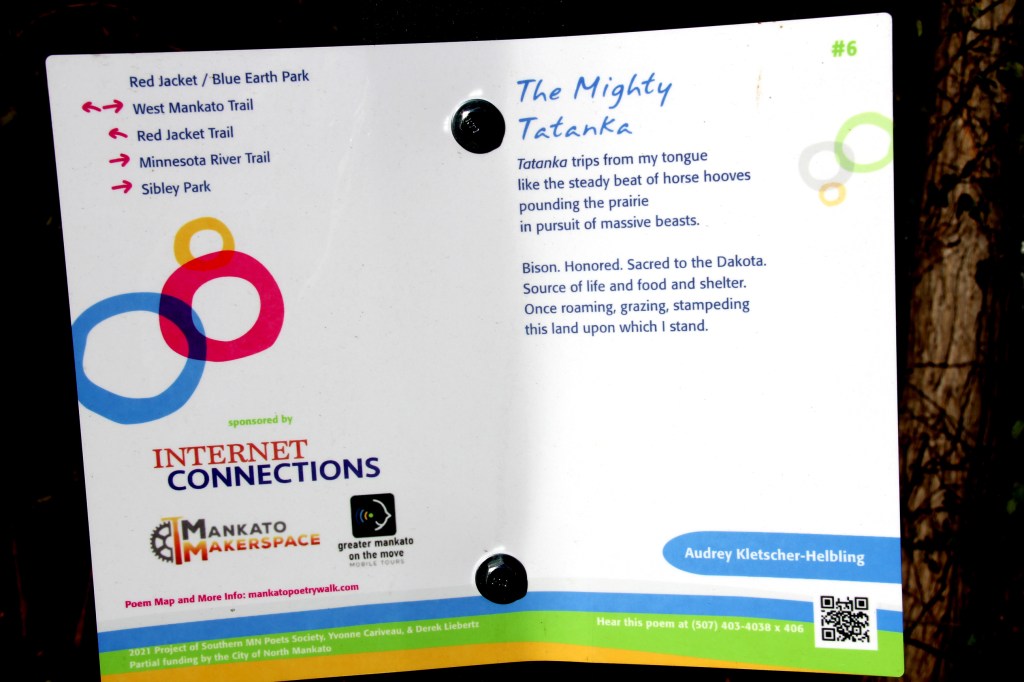

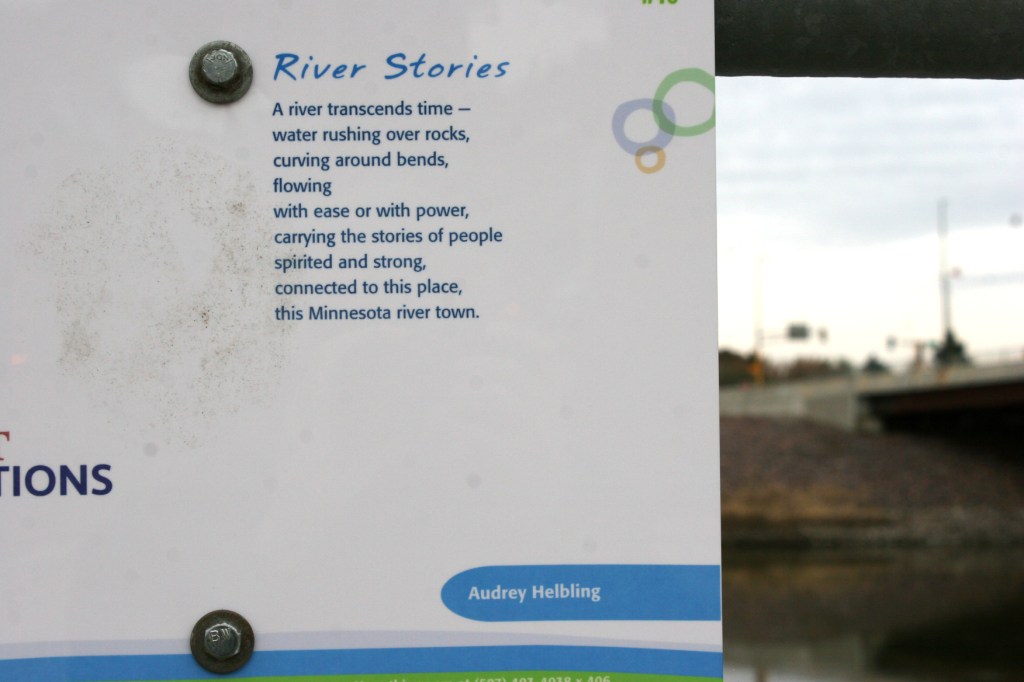

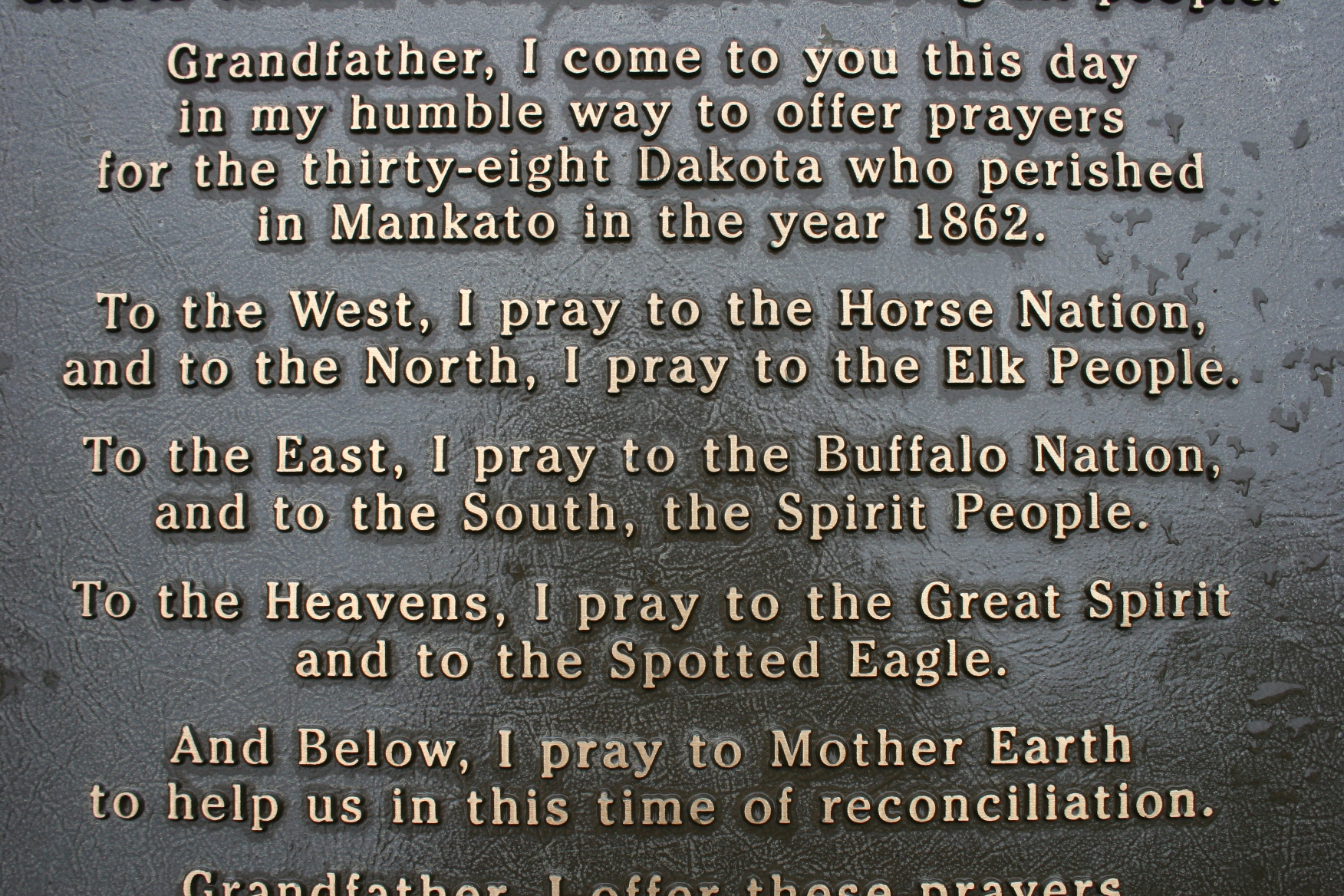

I, too, write poetry and am a widely-published poet, although certainly not as much as many other Minnesota poets. From anthologies to a museum, from the Mankato Poetry Walk & Ride to poet-artist collaborations, billboards and more, my poems have been out there in the public sector. Perhaps the most memorable moment came when a chamber choir performed my poem, “The Farmer’s Song,” during two concerts in Rochester in 2017. David Kassler composed the music for the artsongs.

Poetry has, I think, often gotten a bad rap for being stuffy, difficult, too intellectual and unrelatable. And perhaps it was all of those at one time. Butt that’s not my poetry. And that’s not the poetry of Larry Gavin or of the five We Look West Northfield poets or most poets today. The poetry I read, write and appreciate is absolutely understandable, rich in imagery and rhythm, down-to-earth connective.

When I write poetry, I visualize an idea, a place, a scene, a memory, an emotion, then start typing. The words flow, or sometimes not. Penning poetry is perhaps one of the most difficult forms of writing. Every word must count. Every word must fit the rhythm, the nuances of the poem in a uniquely creative way.

One of my most recent poems, “Pancakes with Grandpa,” was inspired by an exchange between my husband, Randy, and our grandson Isaac, then four. It was printed in Talking Stick 32—Twist in the Road, an anthology published in 2023 by northern Minnesota based Jackpine Writers’ Bloc. It’s a competitive process to get writing—poetry, fiction and creative nonfiction—in this collection.

So, in celebration of National Poetry Month, here’s my pancake poem, penned by a poet who doesn’t particularly like pancakes.

Pancakes with Grandpa

Batter pours onto the hot griddle,

liquid gold spreading into molten circles

molded by the goldsmith.

The collectors eye the coveted coins

that form, bubble, solidify

in the heat of the electric forge.

Appetite fuels imagination

as Grandpa’s coins fire

into golden brown pancakes.

Piled onto a plate, peanut butter spread,

syrup flowing and a nature lesson

in maple tree tapping.

The four-year-old forks the orbs.

“Peanut butter pancakes make me happy!”

he enthuses to the beaming craftsman.

© Copyright 2025 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Commentary: No longer free to speak, to… April 11, 2025

Tags: college campuses, commentary, detained students, Freeborn County, freedom of speech, international students, Mankato, Minnesota, Minnesota State University Mankato, opinion, protests, student newspaper, The Reporter, visa revoked

IN THE 1970s, students at my alma mater, Minnesota State University, Mankato, protested the Vietnam War. Today MSU students are protesting the detainment of an international student and the revocation of visas for five others who attend this southern Minnesota college where I studied journalism.

US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has also detained a student from Riverland Community College in Austin, Minnesota, and from the University of Minnesota in the Twin Cities. Other international students from colleges across the state have also had their visas revoked. The same is happening at college campuses throughout the country. Students snatched off the street, from their apartments, by ICE. Pffff, gone, just like that with no explanation and no initial access to their friends, families and legal assistance. This does not sound like the United States of America I’ve called home my entire life.

I’m not privy to specifics on why particular international students were targeted. But I have read and heard enough reliable media reports to recognize that these are likely not individuals committing terrible crimes, if any crime. In most cases they have done nothing more than voice their opinions whether at a protest or via social media. College campuses have always been a place for students to speak up, to exercise freedom of speech, to be heard. To protest.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio has labeled students with revoked visas as “lunatics.” Really? Name-calling doesn’t impress me. Nor do actions to intimidate, instill fear and silence voices.

I’m grateful that student journalists at The Reporter, the Mankato State student newspaper where I worked while in college, are aggressively covering this issue. In particular, I reference the article “SCARED TO LEAVE MY HOUSE’—Mavericks react to ICE-detained student, what’s being done by Emma Johnson. She interviews international students who, for their own protection, chose to remain anonymous. It’s chilling to read their words. Words of fear. Words of disbelief and disappointment in a country where they once felt safe and free. The place where they chose to pursue their education, jumping through all the necessary legal hoops to do so. And now they fear speaking up and are asking their American classmates and others to do so for them. So I am.

MSU students, staff and community members have rallied to support their international community and to voice their opposition to ICE’s action. In neighboring Albert Lea, where the MSU student is being held in the Freeborn County Jail, a crowd gathered on Thursday to protest ICE action against international students. Of course, not everyone agrees with the protesters and it is their choice to disagree. They can. They are not international students here on visas.

I should note that the sheriffs in Freeborn County and four other Minnesota counties—Cass, Crow Wing, Itasca and Jackson—this week signed agreements to cooperate with ICE.

These are troubling times. In my life-time, this has always been a nation where we’ve been able to freely express ourselves, where that freedom has been valued. We can agree to disagree. Respectfully. Without name-calling. Without the fear of suppression, retaliation and/or imprisonment. But I see that changing. Daily. And that, my friends, is cause for deep concern.

#

NOTE: I welcome respectful conversation. That said, this is my personal blog and I moderate and screen all comments.

© Copyright 2025 Audrey Kletscher Helbling