U.S. Army Cpl. Elvern Kletscher, my father, in the trenches in Korea.

WHEN I CONSIDER Veterans Day, I think beyond a general blanket of gratitude for those who have served, and are serving, our country. I see a face. I see my soldier father, an infantryman on the battlefields of Korea and recipient of the Purple Heart.

My dad carried home a July 31, 1953, memorial service bulletin from Sucham-dong, Korea. In the right column is listed the name of his fallen buddy, Raymond W. Scheibe.

My dad, Elvern Kletscher, died in 2003. But his memory remains strong in my heart as do the few stories he shared of his time fighting for his country. He witnessed unspeakable, violent deaths. And, yes, he killed the enemy, often telling his family, “It was shoot or be shot.” I cannot imagine shooting someone so near you can see the whites of their eyes.

My father, Elvern Kletscher, on the left with two of his soldier buddies in Korea.

Atop Heartbreak Ridge, Dad picked off a sniper who for days had been killing off American soldiers. He suffered a shrapnel wound there.

But his wounds ran much deeper than the physical. His wounds stretched into a lifetime of battling post traumatic stress disorder, long unrecognized. He told stories of diving to the earth when a neighbor fired at a pheasant, the sound of gunfire triggering all those horrible war memories. The neighbor laughed. Likewise, guns shot at a small town parade sent him ducking for cover.

My dad’s military marker in the Vesta City Cemetery. Minnesota Prairie Roots file photo.

I can only imagine the demons my father fought. You cannot walk away from war-time death and violence unchanged. Only much later in life, as the decades passed and awareness of PTSD grew, did my dad find some comfort in talking to other vets with similar experiences.

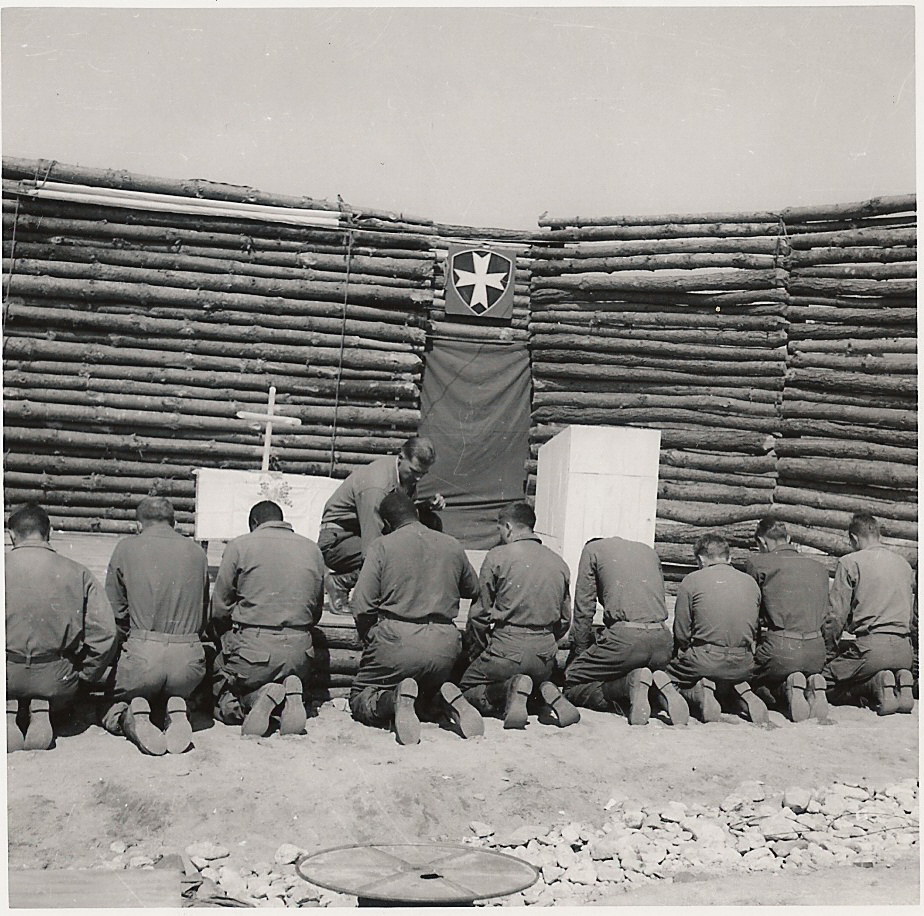

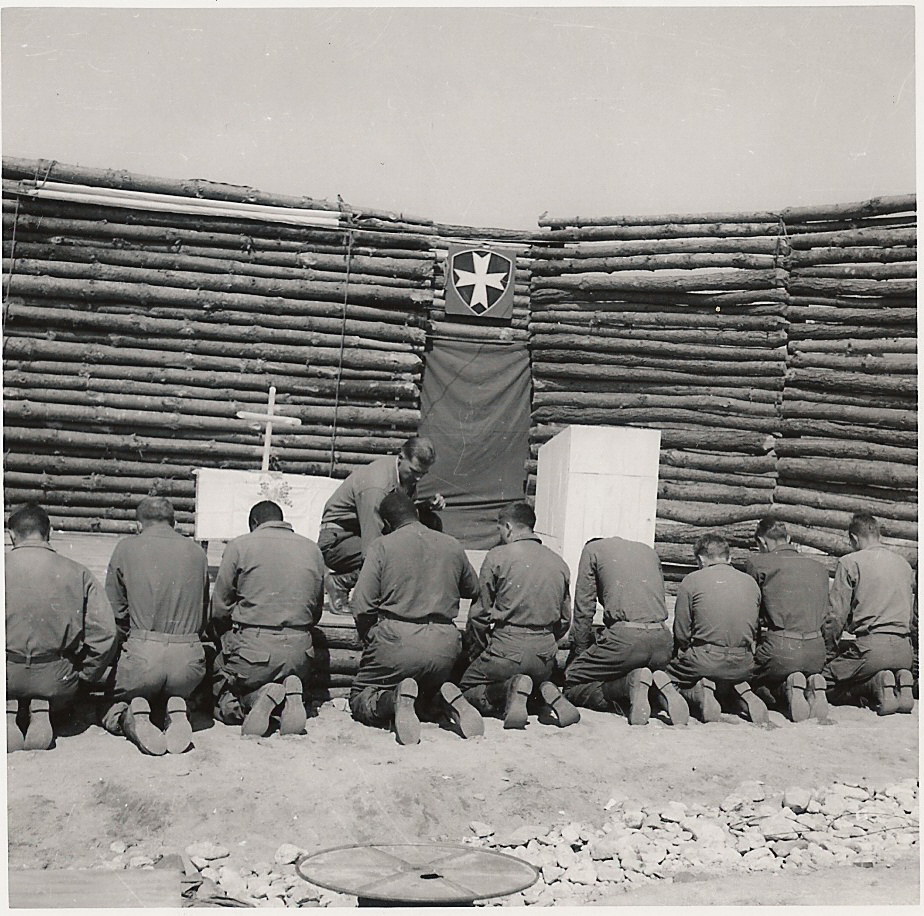

Soldiers receive The Lord’s Supper in Korea, May 1953. Photo by my soldier father, Elvern Kletscher.

Dad’s strong faith also pulled him through his emotional turmoil, during and after war.

Now, as I look back, I wish I had been more understanding, more grateful. But I can’t change that. Rather, I can choose to honor my dad by writing, an expression of the freedom he fought to preserve.

I wrote a story (“Faith and Hope in a Land of Heartbreak”) about my dad’s war experiences in this book, published in 2005 by Harvest House Publishers.

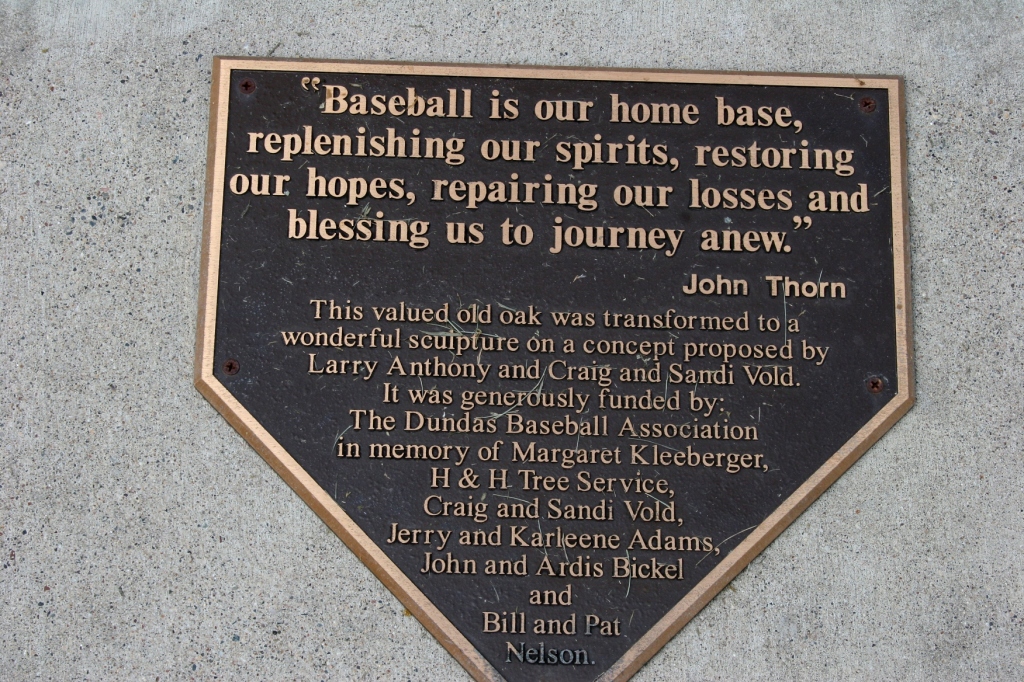

As a writer, I hold dear the value of my freedom to write. No one censors my writing or tells me what to write. I treasure that. I cringe at the current overriding criticism of the press in this country, the constant allegations of “fake news.” I worry about this negative shift in thought, the efforts to suppress and discredit the media. My dad fought to keep us free. And that freedom includes a free press.

That struck me Thursday evening as I gathered with 13 Faribault area writers at a Local Authors Fair at Buckham Memorial Library. Here we were, inside this building packed with books and magazines and newspapers and more, showcasing our writing. No one stopped us at the door to check if our writing met government standards. No one stopped us from selling our books. No one stopped us from engaging in free conversation with each other and with attendees.

I am grateful to those who assured, and are assuring, that I will always have the ability to write without censorship in a country that still remains free.

© Copyright 2017 Audrey Kletscher Helbling

Recent Comments